Our students are “Zoomed” out. This much is true. Perhaps one of the worst moves we could make this fall is to inundate them with even more digital learning. I suspect this will happen anyway, though, as myths of learning loss are rampant throughout education currently. Some have reframed learning loss in terms of learning recovery or acceleration. But make no mistake: each of these terms is deficit-based (Moll et. al., 1992), causing harm to our students and tempting schools to turn to digital solutions promising efficient recovery of “lost learning.”

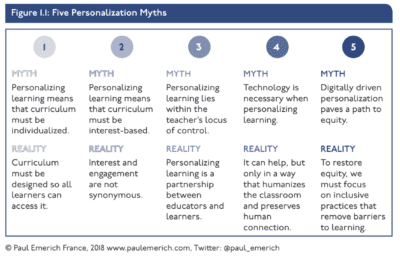

Moreover, schools will be looking to “recover” or “accelerate” this “lost learning” on an individualized level. This is more commonly (albeit inaccurately) known as personalized learning, where educators deliver individualized curriculum through digital means. But this mainstream definition of personalization falls victim to the many myths about personalized learning, all of which I outline in my book Reclaiming Personalized Learning: A Pedagogy for Restoring Equity and Humanity in Our Classrooms.

From Reclaiming Personalized Learning: A Pedagogy for Restoring Equity and Humanity in Our Classrooms

The greatest misconception about personalized learning is that learning must be individualized to be personalized. But this is not only untrue; it’s also unsustainable. The thought of making individualized learning plans for each of our students is very daunting. We may feel like we have no choice but to turn to digital adaptive programs. The costs of these programs, however, outweigh their perceived benefits.

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

First, adaptive programs isolate students

I spent three years working for an education technology company in Silicon Valley, partnering with technologists to build personalized learning tools for the classroom. We hypothesized that learning would be more personalized if students had individualized playlists of activities. While it’s true that our students had highly individualized learning plans, it was also true that the degree of individualization was isolating, making it very challenging—and at some points, impossible—for them to collaborate with their peers.

In order for learning to be personalized, it needs to be humanizing. We know that learning is a social activity. We know that students learn best when they can engage in dialogue and discourse, co-constructing knowledge with their peers. Resorting to web-based, adaptive programs that send students digital content takes away these opportunities for rich dialogue, not only because they are interacting with a screen, but also because each student is working on a different activity. After all, how do you co-construct knowledge with a neighbor if you are working on something different?

Adaptive programs track students

There are more urgent equity concerns when it comes to leveraging web-based adaptive tools for personalized learning. It creates different tracks of students, widening gaps in opportunity to rigorous learning experiences.

We must remember that web-based, adaptive technologies operate off of algorithms. These algorithms quantitative in nature, reducing our students and their learning down to a number; they are also laden with a test-centric bias that harms far more students than it helps. Take, for instance, a third-grade student who, according to the algorithm, is currently working at a first-grade level. The program will provide them with first-grade level content, while many of their peers will receive third-grade level content or higher, creating a high-tech, individualized tracking system and exacerbating gaps in access to grade-level content.

Students are the ones who bear the brunt of the consequences of tracking. As educators who value equity and inclusion, we must find more inclusive ways to meet students’ individual academic needs.

Adaptive programs chip away at belonging

The impact of social isolationism and tracking expand beyond inequitable access to rigorous content; they also chip away at sense of belonging in the classroom. Too often, we define educational equity in terms of access to content within a given child’s zone of proximal development. We must expand our definition of equity, remembering that community, connectedness, and a sense of belonging are critical to giving each student what they need.

In order for learning to truly be personal and equitable, students must feel a sense of connectedness to the classroom. They must know or feel that they are a part of something greater than themselves, as this provides a sense of purpose to learning. When students face screens more than they face their peers, we send the implicit message that content consumption is more important than community or belonging—and as a result, we dehumanize our classrooms, our pedagogy, and worst of all, our students.

Humanizing personalization

It’s okay to advocate for personalization this fall, especially as we try to heal from a traumatic year. But we have to remember two things when doing so. First, remember that individualized learning and personalized learning are not synonymous. Second, advocate for a personalized pedagogy that humanizes our students and their learning. Doing so will ensure connectedness instead of isolation, equitable learning instead of tracked learning, and inclusive classroom cultures where all students know they belong.

How do we do this?

- Center students’ humanity. Spend time building community in class meetings, conduct identity studies (Ahmed, 2018), and spend time focusing on learning habits that promote their independence (Hammond, 2014) as learners.

- Redefine success. Learning should not be about content consumption. Success in our classrooms should not be reserved for students meeting grade-level targets at year’s end. We need to humanize assessment in our classrooms, leveraging student portfolios and qualitative reflections so students can own and find pride in the achievements that can’t be quantified on a standardized test.

- Teach in three dimensions. Individualizing learning isn’t necessarily a bad thing if it is contextualized by a healthy learning environment that keeps kids connected to their peers. Balance individualization by personalizing within whole-group and small-group learning.

- Maximize human connection. It’s not that technology is all bad. It’s just that we over-use it, quite literally dehumanizing our pedagogy and replacing it with machines. Equitable learning can happen while students are collaborating on the same tasks, leveraging a practice called complex instruction (Cohen & Lotan, 1997; Boaler, 2015).

If we move away from the deficit framing of learning loss, learning recovery, and learning acceleration, we see that we actually face enormous possibility for the fall. We have a chance to use the pain from the prior year as a reminder that humanizing learning and keeping our students connected to one another matter more than anything else.

Want more articles like this? Make sure to subscribe to our newsletters.