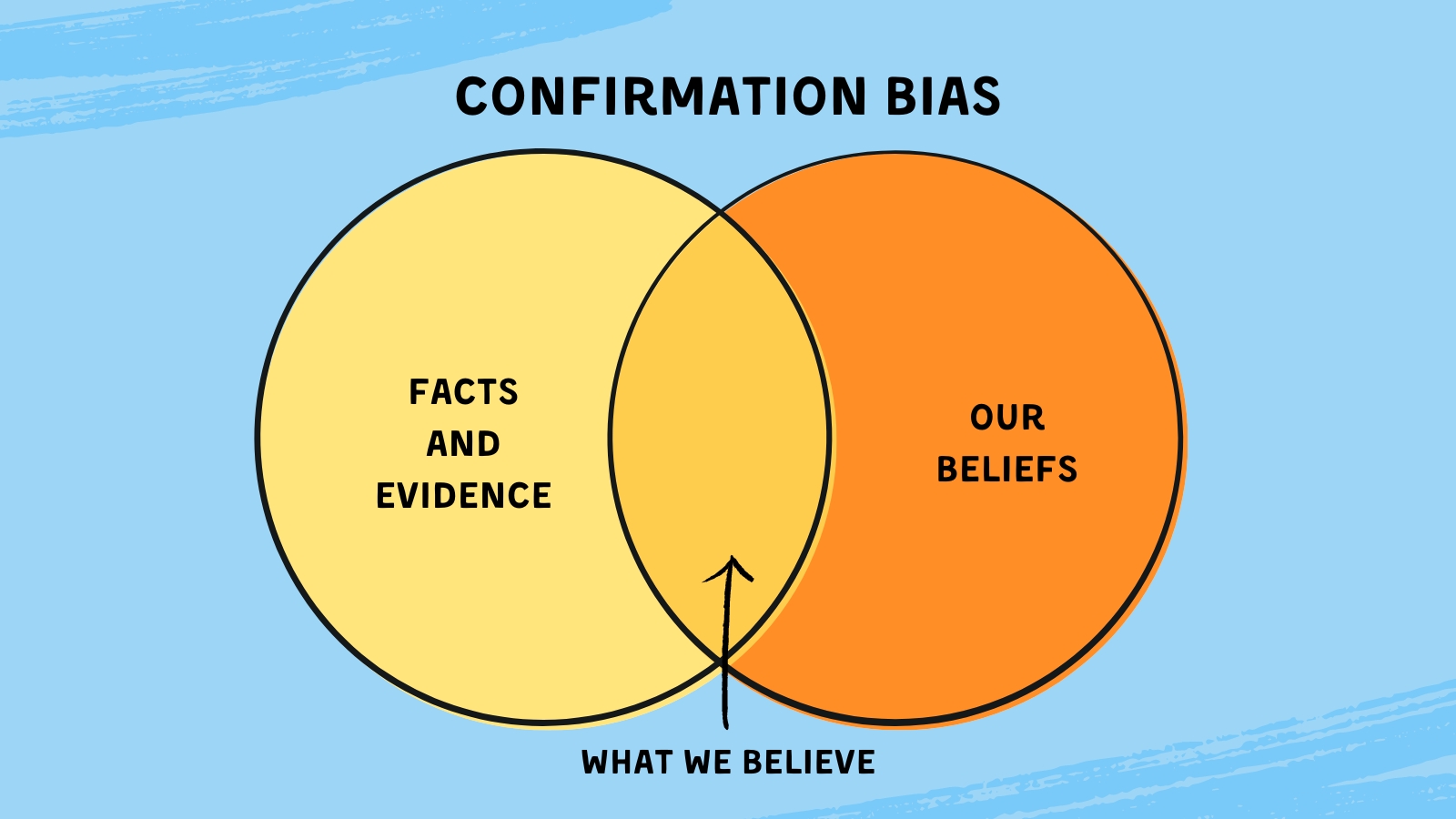

As humans, we want to be right. Being right feels good! But watch out: Our brains tend to unconsciously prioritize information that fits what we already think and minimize anything that suggests differently. Psychologists call this tendency to “confirm” what we already believe “confirmation bias.”

What is confirmation bias?

Confirmation bias is a neurological adaptation that helps our brains more efficiently filter the enormous amount of input we receive. In her book Thinking 101: How To Reason Better To Live Better, Yale psychology professor Woo-kyoung Ahn explains confirmation bias as an evolutionary adaptation to “conserve our brain power.” It can impact what we pay attention to, how we interpret it, and what we remember (or don’t) about our experiences.

Confirmation bias constantly sneaks its way into our daily lives. We’ve all congratulated ourselves upon seeing a reference to research that confirms a health habit we already have. We might even go searching for it without realizing. Think of the different results you’d get by keying in “benefits of hiking” vs. “hiking risks.” Plus, how often do you roll your eyes at a suggestion that you shouldn’t eat or do something you love?

The effects of confirmation bias can range from superficial to devastating. Consider the potential bearing of confirmation bias on criminal investigations. It could cause law enforcement officers to more enthusiastically pursue or consider evidence that fits with their prejudice toward a certain suspect profile, maybe even leading to a wrongful conviction.

3 Reasons Teachers Need To Know About Confirmation Bias

Being aware of the human tendency to confirm what we already think can help us better understand our own teacher brains, our colleagues, and our students.

1. Confirmation bias influences how you relate to your students and colleagues.

The idea that what we expect of students impacts their outcomes has been so extensively researched, it has its own name: Teacher Expectancy Effect. John Hattie, esteemed distiller of education research, noted the substantial impact of teacher expectations across many studies. He says, “The most important thing for teachers to do is to have high expectations for all students. This means not labeling students (as ‘bright,’ ‘strugglers,’ ‘ADHD,’ or ‘autistic’). …” Unconsciously looking for certain outcomes that fit what we expect—and then reinforcing them with our responses—can turn our expectations of students into self-fulfilling prophecies.

It isn’t just our perceptions of students that can get clouded by confirmation bias. Just like doctors can pay more attention to symptoms that fit with a diagnosis they already suspect, having preconceived ideas about whether or not a colleague is strong at teaching reading, adequately prepares students for the AP exam, or has effective classroom management skills could prompt us to zero in on evidence that fits our theories and discount what doesn’t. This is especially important to consider for those in the position of coaching or evaluating others.

2. Confirmation bias can make change harder.

Teachers have new demands made on them all the time. Confirmation bias can easily drive our gut reactions to proposed or required changes at school. If a new science of reading curriculum mandate reinforces what we’re already doing and loving, great—confirmation bias is likely to help us believe in it. If it’s unfamiliar, we’ll probably take it with a generous dose of teacher-tired skepticism. (Is it that pendulum swinging? Again?) We might only halfheartedly implement it or be extra-attuned to examples that suggest something isn’t working.

Looking to educational research for guidance can help, but even that can get sticky. One analysis of teachers’ feelings about educational research in Germany found they were more likely to trust research that confirmed their prior beliefs.

3. Students’ brains want to be right too.

Confirmation bias, when it goes unchecked, can get in the way of kids learning new information. Think about a kindergartner heading into a plant unit. Maybe they’re 100% sure that planting a jelly bean will grow a jelly bean tree. They can easily cling to that idea with all their candy-loving heart. (Disclaimer: I live with this former kindergartner.) This can still happen—and get less cute and more problematic—as students age. (Just check out Teachers Are Sharing the Surprising Things Their Teenage Students Don’t Know.)

How To Counteract Confirmation Bias

Working to manage confirmation bias can be a teachable moment for us and our students too. Here are some actionable steps to take.

Lean on data.

It’s essential to check our confirmation bias at the classroom door when we’re drawing conclusions about what students can do and what they need. Having ample data at our fingertips makes this easier. Approaching data analysis with a curious attitude can help you objectively take in whatever it shows you. Maybe you’ll be surprised!

Consume research with care.

Education research is an invaluable tool to help us grow as teachers. But we have to be careful not to pick and choose only the research that reinforces what we want to be true. One strategy to balance our research consumption is to seek out meta-analyses. These studies integrate the data from lots of smaller studies on the same topic. We can also get smarter about evaluating whether the latest educational research is legit. That way we can avoid getting sidetracked by less reliable studies. Finally, we can force ourselves to research more than one hypothesis. That can help make sure we don’t discount an important alternate perspective. (While we’re at it, let’s teach our students to do this too!)

Make confirmation bias part of classroom conversation.

We can teach kids about confirmation bias, and we can foster habits and give them experiences that help offset it. My son watered and watched a jelly bean in our garden for a whole spring. Eventually he came to the hard realization that even though it had the word “bean” in it and resembled a seed, it would never grow into a lifetime supply of jelly beans.

We can highlight examples for kids of confirmation bias getting out of control throughout history. Think about the Salem witch trials or Columbus “discovering” America, among countless others. We can build “myth-busting” into any curriculum unit. Acknowledging common misconceptions (and letting kids know they aren’t alone or dumb for having them) lets us help kids revise their ideas so new learning can stick.