Learning styles are everywhere. It’s the concept that each student has a stable, consistent way they take in, organize, process, and retain information, and that by teaching using a student’s learning style, they will learn more. When someone tells you they are a “visual learner” or they didn’t understand the presentation because they’re an “auditory learner,” that refers to learning styles. One study found that more than 90% of teachers across five countries agreed that students learned better when taught using their learning style. But that doesn’t mean this is best practice.

The most common learning styles are VARK:

- Visual

- Auditory

- Reading and writing

- Kinesthetic

So, based on the theory of learning styles, if I were a “visual learner,” I would learn best when presented with information in a visual format (pictures, maps). But if I were an “auditory learner,” I would learn the same information best when the information is told or described to me. This would be fine if research supported it. And as of right now, the research just isn’t there. Even more, relying on learning styles can limit how we think about teaching and learning.

Why it’s time to move away from learning styles

The idea is enticing, but it’s time to move on. Yes, students have preferences and every student is different, but that doesn’t mean they have different learning styles. Here’s why we should take a step back from learning styles:

1. There’s no research base to support it

There is not sufficient, empirical evidence that learning styles are a) a thing and b) that using learning styles improves student achievement. When learning styles go through the research wringer, it just doesn’t hold up. Put simply, teaching to a specific learning style does not improve academic outcomes.

2. Learning styles are difficult to measure

There is no one definition of learning styles. In fact, there are more than 50 proposed learning styles, including the learning style of “using a cell phone.” The sheer number of definitions makes it difficult to study. When we are assessed for learning styles, what we are expressing are our learning preferences, which are subjective and typically not accurate. And many teachers use various modalities throughout a lesson, so isolating a specific learning style is difficult to do in the classroom anyway.

3. How we prefer to learn changes over time

It’s easy to poke holes in the theory of learning styles when thinking about how we learn different tasks. We are all kinesthetic learners when trying to learn how to ride a bike. Learning styles change depending on what we are learning—we may enjoy learning history from a textbook but prefer visual models when learning geometry. And if learning styles change depending on the topic, then they are not useful. How can we plan instruction if a student’s preferred learning style is always changing?

4. Learning styles are too simplistic

Learning styles assume that students are passive, waiting for information in their learning style to come their way. But the best learning happens when students are actively engaged and can connect new learning with what they already knew.

What do we do instead?

All this to say, the theory of learning styles is a myth. So, what do we focus on instead?

1. Focus on what works

We expect some commonalities among students. For example, there are basic aspects of the brain that are common from student to student (how the brain processes short- or long-term memory, for example). And we know that certain educational approaches are effective, regardless of learning style. For example, phonics instruction is the best way to teach students to read, regardless of learning style.

Learn more: How To Figure Out if the Latest Education Research Is Legit

2. Model, lead, test

In order to master something new, we need to see it done correctly, be led through it with feedback, and practice it on our own. Yes, this is the core of direct instruction, but it’s how many things are taught, whether you’re teaching yourself to knit using YouTube videos or teaching students to separate a strand of DNA in a lab.

3. Differentiate

We all have preferences, and some students will have specific learning needs. Differentiate instruction to provide a variety of entry points for a topic, and various ways for students to engage with content.

Learn more: 35+ Differentiated Instruction Strategies and Examples for K-12

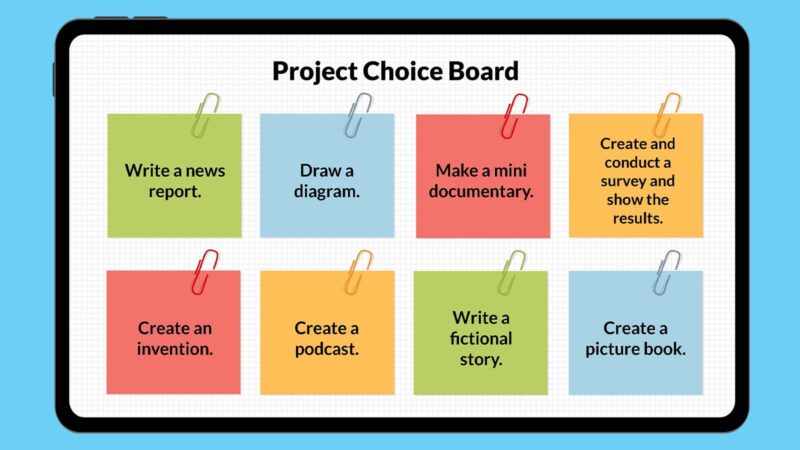

4. Use choice boards

Since research on learning styles is often self-reported, what we are actually talking about is what we like. I like to read, but am I a reading-style learner? And do I want all my information to come to me in the form of books? Will turning on subtitles increase my learning? Not necessarily. Use choice boards to let students self-direct their learning according to their preferences, without worrying about learning style.

Learn more: Free Choice Board Bundle

5. Focus on sustaining attention

We know that learning requires students to pay attention to and engage with one thing for a sustained amount of time. Providing lots of opportunities to engage with content leads to more learning. And those experiences can vary, from hands-on to reading to listening.

6. Engage the brain

Bring multiple modalities into learning so students are fully engaged and making connections between what they know and new information. For example, providing visuals and audio, as a good PowerPoint presentation does, engages more of our brains and helps students retain more information.

7. Build relationships

Focusing too much on learning styles also leaves out the role of the teacher and student. Learning is complex, and a lot depends on the connection between the teacher, student, and content.