There are days when it feels like all we do in the classroom is solve conflicts. “He took my baby doll.” “She knocked over my tower.” “She knocked over my tower again!” “She hit me.” “He won’t let me play.” “We don’t want her to play with us.” On the one hand, it sounds like a long list of problems. On the other, we know that what we’re really facing is a long list of teaching opportunities.

So much of what early childhood education is about is learning to share your space with people who are not your family. When we can teach kids how to resolve their own conflicts, we’re teaching them how to be successful in life. Here are eight tips to help kids solve their own problems at playtime.

1. Create a classroom environment that minimizes conflict.

Early childhood educators spend more time creating their learning environment than teachers at any other grade level. We know that classroom setup matters to our youngest learners. Providing kids with plenty of room to play and plenty of materials to play with can minimize opportunity for conflict. Last year, we discovered that many of our kids really enjoyed playing with dolls. As more and more fights erupted over who got which baby to play with, we realized that our collection of dolls had dwindled to two! No wonder the kids were constantly fighting. Two baby dolls for eight kids is simply not enough.

The easy solution was to round up a few more babies. Once we boosted our collection, conflicts diminished. It can work the same way with space.The year before last, we had several students who were capable of building gigantic, complex structures in the block area. But knocked-over towers were a constant complaint. Once we expanded our block area so that more kids had room to build big structures, conflicts were dramatically reduced.

2. Create solid routines.

Like all of us, kids do better when they know what to expect. A predictable schedule and routine go a long way toward preventing conflict. Early childhood expert Betsy Evans says, “The routine is the child’s clock.” It’s how they track their days. A child who knows that more outside time comes right after lunch might be more willing to share the tire swing because he knows there will be more outside time, which means more tire-swing time. He’s had experience hopping off the tire swing for a bit and then being able to jump back on after awhile, so he feels confident in taking a break.

We had one year when, due to space constraints, a predictable schedule was really challenging to implement. The teachers were only a step ahead of the children, and as a result, we were all on edge. None of us knew what to expect on any given day. Did we have a second outside time or was this our last one? No one knew, and no one could relax. Predictability helps us all feel safe, which helps us all handle emotional situations better.

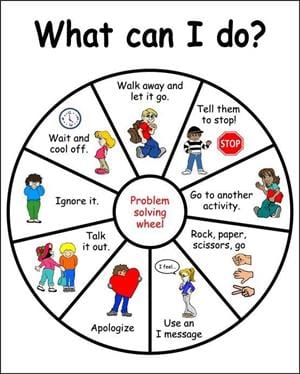

3. Teach them a process for problem-solving.

No matter how well we prepare our environment, and even when we have the perfect, developmentally appropriate schedule, we all know that there will still be conflict. Using a consistent problem-solving approach can help young kids learn to solve their own problems. There are a variety of different processes you can implement. Most of them follow a similar approach. One pre-kindergarten classroom I taught in used a choice wheel similar to the one shown here.

(Source: Pinterest)

We’ve also seen teachers ask students to work through a series of consistent steps, like these from Childhood 101. If you follow a consistent pattern with kids each time you help them navigate a tricky situation, even little ones will pick up on that pattern and then begin applying the strategies they’ve watched you use. This video shows teachers working with preschoolers to navigate a specific series of steps in a problem-solving process. You can tell that the children have worked through the steps before because they seem to know exactly what is expected.

[iframe src=”https://player.vimeo.com/video/223177087″ width=”640″ height=”480″ title=”Teach feeling words.”]

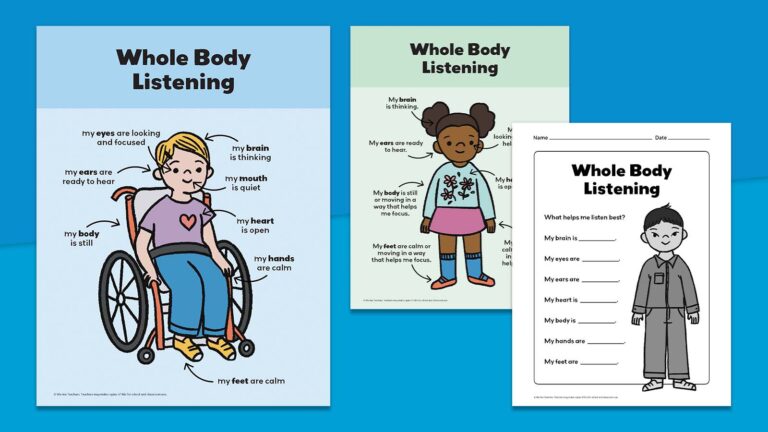

4. Teach feeling words.

When kids are young, sometimes conflicts erupt simply because they don’t have the vocabulary to effectively express themselves. We can help them learn key words when we model their use. You can see an example of a teacher labeling feelings in the video above. In our classroom when we see two kids fighting, after we stop any potentially hurtful situations, we start by making some observations. “Ellie, your face tells me that you are feeling mad.” “Sophie, your face tells me that you are feeling sad.” Sophie may have been so wrapped up in her sad feelings that she didn’t think to name them. She also probably didn’t notice Ellie’s mad feelings. When we talk to children this way, we’ve helped call their attention to words that they can use to describe their feelings at a later time when perhaps they find themselves handling a conflict without teacher support.

(Source: Pinterest)

5. Ask concrete questions.

It’s so easy to confront a child with, for example, “Why did you hit her?” Sometimes kids will know the answer, but other times, even if they know the answer, they won’t really be able to express their answer in words. Concrete “what” questions will help you get your answers more quickly than “why” questions. The concept of “why” is often too abstract for young children. Do take the time to ask questions though. More than once, I’ve found myself in the awkward position of having made incorrect assumptions about child behavior because I didn’t take time to investigate.

6. Involve the children in finding a solution.

Once you have the facts, it’s time to move toward a solution. If you involve children in the problem-solving process, you’re giving them the practice and tools they will need to solve a problem on their own the next time they’re embroiled in conflict. Ask children for their ideas. You might be surprised by what they come up with. Their solutions are sometimes more workable than our own. For example, in the second half of the video above, when Pedro is looking to fit himself into the crowded table, I’ll admit, my first instinct would have been to ask Pedro to find a new place to sit. Instead, this teacher chooses to help the children work through their own conflict. Pedro and his classmates come up with a workable solution, and not a single tear is shed.

7. Don’t force an apology.

This one doesn’t always come naturally. Most of us have been taught since we were small that if one offends, one should apologize. And while that remains true, what we know now as adults is that only a heartfelt apology carries weight. An insincere apology has the potential to be worse than the original offense. When we force kids to apologize for errors for which they may not actually feel sorry, we are teaching them to offer insincere apologies. The fact is, 4-year-old Emily may not be sorry for hitting Lizzie. Emily is still really mad that Lizzie took the doll she was playing with and may feel like hitting was her only option. Our first job is not to ensure that Emily make amends for her error but to help Emily learn to express her frustration in a manner that is appropriate for school. Chances are good that genuine contrition will come on its own, once we have helped Emily resolve her issue with Lizzie. What’s more, we might also get a genuine apology from Lizzie, too, about the initial baby-swiping that started the whole conflict.

8. Remember that learning to resolve conflicts is challenging.

There are mediation attorneys who charge hundreds of dollars per hour to help adults resolve conflicts. It’s not an easy skill to master. We certainly shouldn’t expect 4- and 5-year-olds to be experts after a couple of experiences with problem-solving alongside a teacher. I often forget this and find myself asking, “Is she really hitting one of her classmates again? Didn’t we just work through other solutions yesterday?”

In fact, conflict resolution is a skill that takes practice and a little bit of finesse. We need to be prepared to support our young learners with this skill, just like we would support them as they are learning to read and write letters. We don’t expect perfection, and we do expect a fair amount of repetition. Some kids will grasp the concepts more easily, some will need more support. It is our job as teachers to be there to guide them as they progress in their learning and hopefully learn to negotiate problems all on their own.