“Stop having them read The Great Gatsby.” The weight of this statement hit me hard. First, because it came from a former student as we sat over coffee, catching up on life. He was the type of student described more than once by colleagues as, “Too smart for his own good,” and one who challenged me on multiple levels as a teacher. The second reason his directive to stop teaching a classic: We had bonded over our mutual love and respect of that very novel, The Great Gatsby. He had even gifted me an anniversary copy, with a note describing how well he connected with Nick Carraway’s musings on being “both within and without.”

So, why was he so persistent that I stop teaching this classic that he and I both loved? One reason: Can an adolescent reader really understand and engage with the major themes presented in a novel written by an adult, about adults, for adults? My former student’s answer? “No.” He had hated Gatsby in high school and only came to love and appreciate it after ample life experience, maturing and interacting with the world beyond high school.

After our conversation, I found myself asking, “Am I teaching these classics because I like them, I understand them, I get them?” Let me be overt in writing that, absolutely, I believe young adults are capable of understanding themes in great literature. I believe whole-heartedly that classics resonate for a reason worth studying. But the sub-question is, “Is there a different avenue?” Can these same themes and experiences – these same writing techniques – be accessed and taught through texts that are more relevant to the adolescent experience?

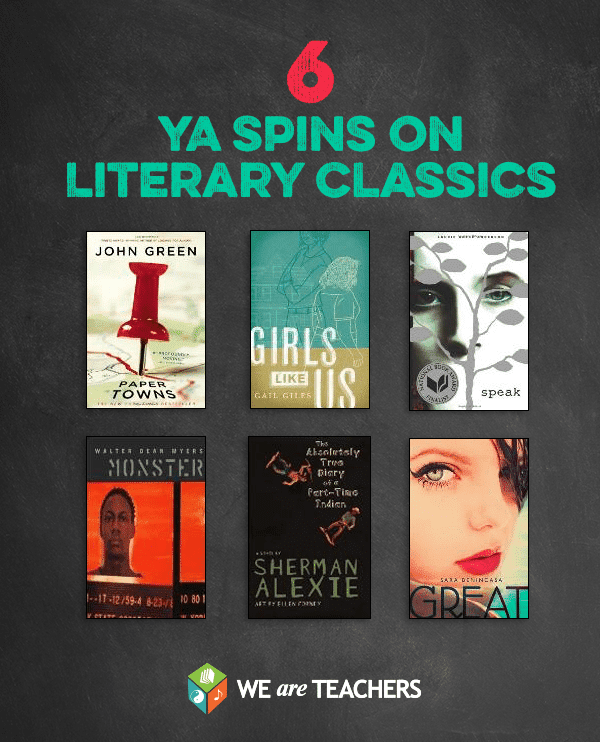

I went on a mission to find out. After months of feverish reading, I’ve come across some great stories, many of which were recommended by current and former students. These stories provide a different avenue to the same destination we often seek with American classics. If you’re a “old-white-dude-literature-purist,” consider using these as supplements or enhancements. If you’re ready to shake it up entirely, do a full-swap out. Either way, your students will benefit from these engaging, modern gems.

Instead of Moby Dick try Paper Towns, by John Green

The connection between Moby Dick and Paper Towns isn’t hard to find: Melville’s classic is alluded to often in Green’s novel, as images of ships and direct references to the Moby Dick are made throughout (The protagonist is assigned the great novel in his Literature class). But, the connections are more than surface-level references. Quentin Jacobsen finds himself on a mission to catch not a great whale, but a girl every bit as grand, rare, and challenging as Ahab’s great white beast. Paper Towns surprised me with how deeply it explored topics of identity and obsession, pushing toward the metaphysical in a way many YA books don’t attempt. Not every student may be ready to tackle the intimidating and dense Moby Dick, so consider Paper Towns as a warm-up row before hopping on the great vessel.

Instead of Of Mice and Men try Girls Like Us, by Gail Giles

Of Mice and Men is often used to focus on the social hierarchy of America in the 1930’s, as characters are read as symbolic of different demographics: senior Americans, black Americans, female Americans, disabled Americans. These same issues of social hierarchy permeate Girls Like Us, which is told from the perspective of two recent high school special education graduates who are thrust into the work world as roommates. The harshness of life, the necessity of friendship, and the power of empathy are just as present in Girls Like Us as in Of Mice and Men. With both novels being easy-to-read for the average reader, you can imagine the depth of discussion in a class that tackles these texts together.

Instead of The Scarlet Letter try Speak, by Laurie Halse Anderson

Only after reading Speak had I read that the story may have been based on The Scarlett Letter. How had I not seen that sooner!? Rather than trudging through the painful descriptions and archaic language of Hawthorne’s great novel, help your students understand themes of isolation, chastisement, and resilience in a modern way that is every bit as thought-provoking as The Scarlet Letter. Melinda, the narrator of Speak, enters high school as a social outcast due to a tragic event at a summer party. Throughout the novel, readers see the damaging effects of isolation, gossip, and abuse. Really, you shouldn’t need an excuse like “supplementing The Scarlet Letter” to have your students read Speak. But, The Scarlet Letter has bored and frustrated American teens for so many decades that I consider it a win-win to replace it with this more modern classic.

Instead of To Kill a Mockingbird try Monster, by Walter Dean Myers

I know you’re still stirred up about how good ol’ Atticus Finch is portrayed in Go Set a Watchman. So, why not take a break from the “sweet girl becomes a sweet woman” classic and have your students tackle the issues of race, justice, and perspective in a different way? Monster is told from the perspective of a black high schooler who is undergoing a murder trial that may put him away for life. Presented as a film script, Monster will make readers analyze their society, their perceptions, and their decisions differently. Not only does it advance our understanding of race, culture, and perspective, it gives a unique spin to the bildungsroman genre, which is often filled with books too cheesy to hold stock with teenage readers.

Instead of The Grapes of Wrath try The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, by Sherman Alexie

The issue of poverty in the United States is more complex than ever, so there’s a reason why The Grapes of Wrath still holds relevance in literature classes. But, for those who still want to explore the implications of poverty and humanity in a way that is more accessible to developing readers, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian is a great option (and one even my most ardent “book haters” love to read). The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian is the story of a teenage American Indian, Junior, who leaves his reservation to find hope at a new school. Both The Grapes of Wrath and The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian feature protagonists who take massive risks to find new opportunities. Both are riddled with tragedy after tragedy. Both demonstrate the power of resilience and companionship while challenging our views of the stereotypical “American Dream.”

Instead of The Great Gatsby try Great, by Sara Benincasa

Great is a reimagined, modernized Great Gatsby. Because it is an intentional rework, it won’t live up to The Great Gatsby‘s brilliance (Reworking an artwork of genius is not easy). However, Great makes an interesting supplement to show how concepts of hope, inauthenticity, and social class might play out in more modern times. The story centers around Naomi’s venture into the wealthy world of trust fund babies from The Hamptons. Each character we meet mirrors someone from The Great Gatsby and more than a few allusions are sprinkled throughout the novel. Even doing a side-by-side comparison between just chapter one of Great and Fitzgerald’s masterpiece will stir up interesting conversations and engage critical thinking.

Got your own recommendations for lighting up a new literary canon? Post your favorite supplements and replacements in the comments below!

Chase Mielke is a learning junkie who happens to have a love affair with teaching. A book addict by night and a teacher and instructional coach by day, he fantasizes about old libraries and fresh Expo Markers. His obsessions with psychology, well-being and cognition often live on his blog, affectiveliving.wordpress.com. Follow him on Twitter @chasemielke.