This October, Pennsylvania senators unanimously passed a bill to end child marriage. And two extraordinary teachers are largely responsible for its success.

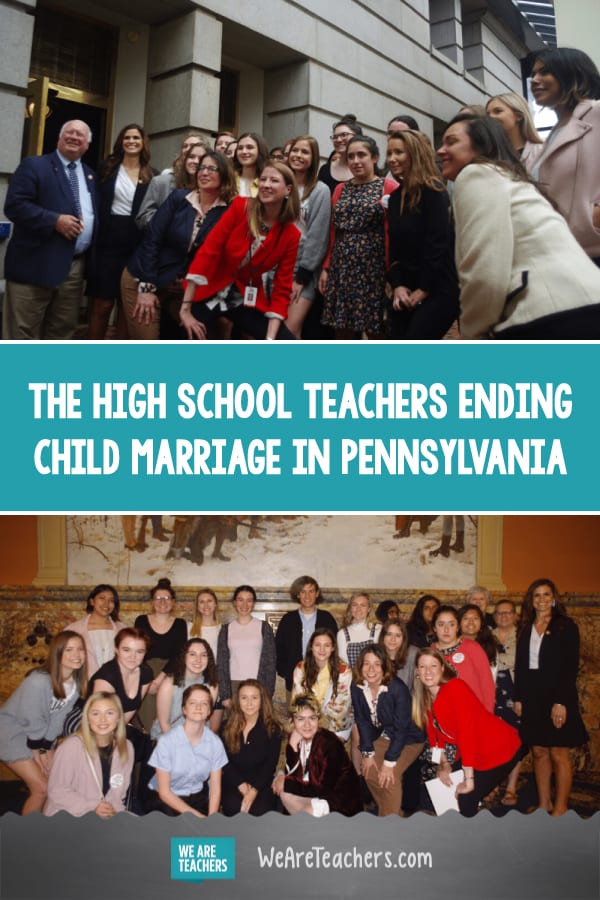

English teacher Daniela Buccilli and social studies teacher Leah Humes started Pennsylvania’s first integrated gender studies class at Upper St. Clair High School in Pittsburgh. After an inspiring class project, the students found themselves speaking with representatives and senators inside the Pennsylvania capitol. The students took their issue all the way to Governor Tom Wolf, who shook their hands and committed to signing the bill when it reaches his desk.

Because of their collective effort, it seems likely that the bill could pass by December 2020 or sooner.

Believe it or not, child marriage is still legal.

You might be thinking, “Wait. Isn’t child marriage already illegal in Pennsylania?” Or, “How did two teachers and their students get involved in changing the law?” Well, it’s a lengthy story that starts with one concise yet unsavory truth: Child marriage is still legal in 48 states.

The marriage age is 18 in the United States. Yet in nearly every state, children can marry due to parental or judicial exceptions. These exceptions make it possible for a minor (as young as 12 in a few states) to marry if a caregiver or judge determines it’s in the child’s best interest. These exceptions are often the “solution” to unplanned pregnancies. And in most cases, it’s teenage girls who marry older men at the encouragement of their parents.

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

From 2000 to 2010, there were 250,000 children married in the US. And census data shows that as of 2014, an estimated 2,323 children between the ages 15 and 17 living in Pennsylvania had been married.

Yet, a married teenager does not receive the full legal rights and protections of adults. In most states, a married child still needs the consent of their caregiver or adult spouse to have a cell phone contract, take out a mortgage, or sign for care at a hospital. Furthermore, if the marriage becomes abusive, a child cannot legally check themselves into a domestic violence shelter without the permission of their spouse or parent.

Students learned about the issue because a nonprofit advocacy group worked with representatives to introduce a bill.

In February 2017, Fraidy Reiss, the founder of the nonprofit organization Unchained At Last, published an op-ed in the Washington Post. The article asks a provocative, yet relevant, question: “Why can 12-year-olds still get married in the United States?” This prompted constituents in Pennsylvania to approach their representatives. The news eventually reached Upper Saint Clair High School, where Alex Roberts, a senior in Humes and Buccilli’s gender studies class, presented on the issue for a class project.

Through Roberts’s presentation, the class learned that child marriage, which affects 12 million children (mostly girls) across the globe, is happening in their very own state. That legislators had introduced a bill to end it mitigated their outrage. But students appealed to their teachers’ moral compass. Could they go rogue, they wanted to know? Take things off syllabus and into the Pennsylvania House of Representatives?

As the teachers of Pennsylvania’s first gender studies high school elective course, Daniela Buccilli and Leah Humes knew their class would set a precedent. But they hadn’t expected to take their students to the capitol. Yet, they knew that they had an opportunity. Together, the teachers decided to show their students that social change is made through informed, intentional action.

Teaching kids about social change starts with helping them determine an appropriate strategy.

“Not all change comes through legislation,” said Humes, a former activist. “It just depends on the issue.”

In the case of child marriage, state representative Jesse Topper had introduced a bill with input from Unchained At Last. Therefore, the most appropriate course of action was to help with timing. So began the push to include the bill in an upcoming committee meeting. That way, students could help ensure it didn’t get lost in the shuffle. But first, Humes needed to activate her students’ critical thinking skills.

“Because it’s the age of Twitter, it’s easy for students to get caught up in political embers,” said Humes. This makes young people feel as though their voice has made a difference when in fact they’ve accomplished nothing. “It can be horrifying as a teacher,” said Humes, whose students innocently suggested social media and Change.org petitions as the most powerful way they know how to get things done. For Humes, her students’ well-intentioned attempts at activism were unacceptable and indicative of a systemic lack of knowledge. “These are smart kids who sat in social studies classes for many years but could not tell you how a bill is passed,” she said.

By looking to past movements and other social justice organizers, students learned how to influence lawmakers.

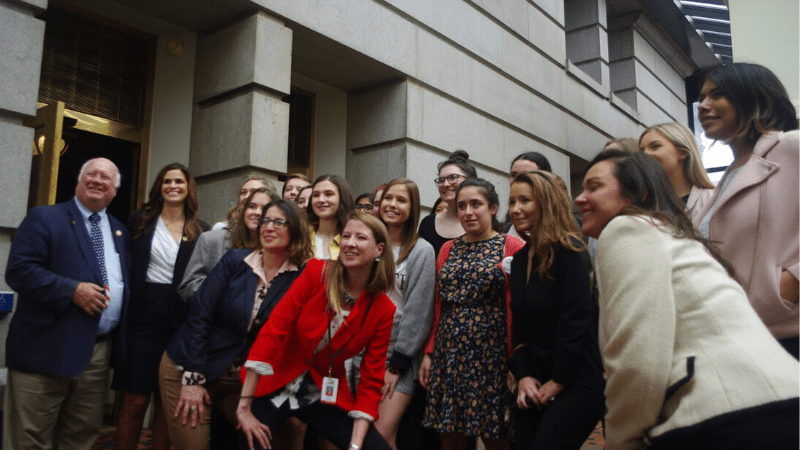

Students, teachers, and chaperones of PA’s first gender studies high school elective course gather in the PA General Assembly after pushing for the unanimous support of HB360 in the House Juidicary Committee.

Humes pulled out the Midwest Academy Strategy Chart, a tool used for political organizing that outlines the various routes constituents can take in order to achieve a particular goal. The chart asks guiding questions to help change-makers determine appropriate stakeholders, governing bodies, and need for public awareness.

Sometimes, said Humes, the most appropriate method of change is through direct action, such as strikes, sit-ins, and boycotts. Other times, action is more about influencing policy makers and shifting the conversation around our existing laws. Humes saw that Unchained At Last was planning to educate the public through a Chain-In protest in Harrisburg, the state capital, after the end of the school year. So she knew the most appropriate way for her students to support existing efforts would be to influence the timing of the bill.

Humes called Rep. Topper’s office and asked: Why had the first version of HB 360 (originally HB 2542) fizzled out? Was it too controversial? Were there ulterior political influences?

Fortunately, none of those were true. In fact, the bill had strong bipartisan support. There was little push back and no major budgetary concerns. It simply arrived too late in the session to receive much attention.

Once the class learned this, Humes grew confident. She told her students, “We’re actually going to do this. We are going to get this passed in Pennsylvania.” Then, said Humes, everyone became “super giddy.”

Literature was an important classroom tool for contextualizing and strengthening the students’ efforts.

One of the benefits of co-teaching an integrated studies class is the support of having two teachers share the responsibilities of leading these complex discussions. Humes took the lead on the activism portion of the project. And Daniela Buccilli led the literature portion to humanize and contextualize the efforts of present-day political change.

“Literature allows us to be speculative and tap into the imagination, which is something activists need,” said Buccilli, who is currently leading the new semester’s students through The Color Purple. Last semester’s unexpected activism project prompted a new batch of enthusiastic students to sign up for integrated gender studies. So Buccilli is incorporating lessons from last semester into this semester’s evolving syllabus.

“When you look at a book like The Color Purple,” she said, “many activists could get stuck on the first page.” Celie, the protagonist, is facing extreme circumstances that rightly inspire a lot of indignation at the state of the world.

“You could not believe her life would improve,” said Buccilli. “But a good narrator walks you through the problem, through the climax, and towards a resolution.” Because Celie takes control of her fate, it is, more or less, a satisfying book, says Buccilli. And activists, who dedicate their lives to addressing problems, navigate heightened political events and ride these climaxes through to a resolution. Thus, they need literature as an example.

English composition also helped students write effective letters to their representatives.

English composition also becomes critical when the civic strategy involves intensive letter writing to representatives, as it did in February 2019 when Humes and the students requested support for the child marriage ban.

Serendipitously, the father of one of the students was hosting a meeting that representative Natalie Mihalek would be attending. Knowing this, Buccilli guided the students in writing very targeted, specific letters asking for one particular thing: Since the bill had bipartisan support, all they needed was to ensure it would make it before the eyes of the House Judiciary Committee—and soon.

So, they wrote letters, said Humes. “We asked Rep. Mihalek if she could talk to the chair of the committee and get HB360 placed on the upcoming agenda.” With such a simple, targeted request, the answer was quite simple. They got a resounding yes. By May, the students were sitting before members of the judiciary committee witnessing HB 360 receive unanimous support. This speaks directly to the power of a well-crafted letter.

Teaching literature and history together sets a powerful precedent for building a new generation of change-makers.

“Literature asks us to think about self-determination and injustice,” says Buccilli. “It is the perfect accompaniment to history, and vice versa. In our integrated studies course, we are not trying to strike a balance between classic literature and contemporary literature. Instead, we look at questions that literature asks about our current world. We are directly finding connections between our experience, the experience of women in the past, including those in our families, and characters [in the] text.”

For a one semester elective course their students read two novels, a dozen poems, and two dozen articles and essays. They consider complicated ideas about gender and justice, ideas that some adults want to avoid.

But, says Buccilli, young people want to be a part of the world in a way that benefits most people. What started as a class project on gender issues led to activism—what the teachers now consider to be a natural outcome of a course designed to teach critical thinking, civic engagement, and social awareness.

These students were part of a global human rights movement.

Humes and Buccilli’s efforts were, and still are, part of a global initiative to end child marriage by 2030 . In the states, Unchained At Last is addressing the issue head on. With progress in Pennsylvania at a momentary pause, Fraidy Reiss is working with legislators in Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Washington, and even in the US Virgin Islands to end child marriage. Here is a map of Unchained At Last’s progress.

If you’re interested in starting an integrated studies program based on the organic model that’s unfolding at Upper Saint Clair High School, you may contact Leah Humes at lhumes@uscsd.k12.pa.us and Daniela Buccilli at dbuccilli@uscsd.k12.pa.us for support.

Have your students ever advocated for policy change? We’d love to hear about your experiences in our WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

Plus, books for teaching about social justice.