It’s hard to think of kids suffering from depression. Teachers, though, know that kids face plenty of challenges from a young age. And like many mental illnesses, childhood depression can have multiple causes that have nothing to do with how “hard” life is.

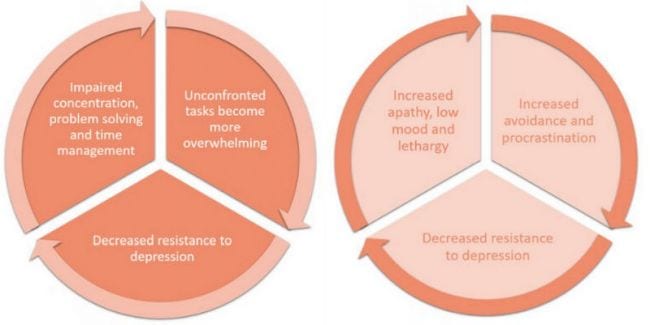

When it comes to childhood depression, teachers play two key roles: identifying the symptoms and supporting kids who face it. Teachers see their students nearly every day and are often quick to notice behavior changes that parents should know about. You might be surprised to learn, however, that teachers can do a lot more than just be a listening ear; kids suffering from depression need help with specific skills, like time management. Here’s what to look for and how to help.

Know what childhood depression looks like.

Via National Alliance on Mental Illness. Get the full infographic here.

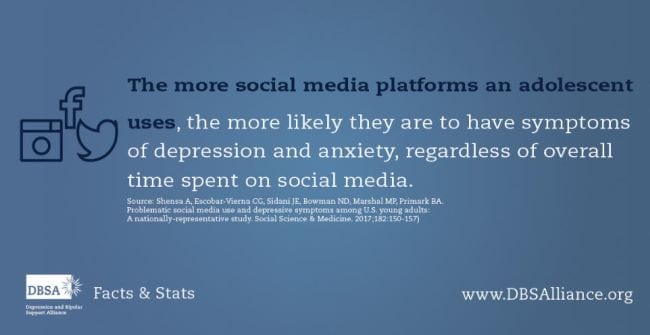

According to the CDC, more than three percent of kids aged three to 17 (nearly two million children) have been diagnosed with clinical depression. That number increases with age; six percent of kids between 12 and 17 have been diagnosed. Kids with learning or behavioral disorders are more likely to experience childhood depression. So are those being bullied, or who have a social media addiction, or a family history of depression, among other causes.

Childhood depression shares many symptoms with adult depression, but some are more common or exhibit differently in kids. Depression is generally diagnosed when some or all of symptomatic behaviors have been present consistently for at least two weeks and when those behaviors are disrupting the person’s daily life. Here are some of the behaviors you might see in the classroom.

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

Irritability and hypersensitivity.

Children with depression can have trouble finding the words to express how they’re feeling. It often manifests in tantrums or frequent crying over small matters.

- Example: Leah receives a B+ on an assignment instead of an A. She balls up the paper and throws it away, then bursts into tears.

Difficulty concentrating or completing assignments.

Depression makes it hard to focus and takes away the motivation to complete tasks. Combined, these symptoms mean that students suffer academically. Teachers are often the first to notice this symptom.

- Example: James has always been a good student but begins missing assignments regularly. When asked, he says he can’t keep track of everything, and it doesn’t seem to matter anyway these days.

Seeming sad, tired, and uninterested in activities they’ve enjoyed before.

Sadness doesn’t necessarily mean frequent crying. It often just looks like general disinterest in things, especially those that used to be fun. Childhood depression often causes sleep disturbances, too, which leads to low energy.

- Example: Angel used to love choir practice and sang to herself while she worked on other things, too. Now she barely participates during choir and is quiet and withdrawn in the classroom. Once, her teacher even found her asleep during silent reading time.

Frequent physical symptoms, like stomachaches and headaches.

Children can have trouble processing their emotions, so they often exhibit physical symptoms instead. Depression itself can cause aches and pains too.

- Example: Chris has been missing school at least once a week due to an upset stomach, according to his parents. At school, he frequently complains of headaches and asks to go see the nurse. His doctor can’t find anything physically wrong with him.

Decreased self-esteem and increased risky behavior.

Kids with depression may talk a lot about how dumb they are or say they’re not worth a teacher’s time. They may also act out in unexpected ways, escalating over time.

- Example: Aria was always a middle-of-the-road student, but usually well behaved. Now she’s failing tests but tells her teacher that’s just because she’s too stupid to learn. She says her teacher shouldn’t spend so much time worrying about her because she’s not worth it. She’s started showing up late to school and was caught vaping at her locker between classes.

These are some of the more common symptoms, but depression differs in children, teens, and adults. Click here for a more complete list of childhood depression symptoms by age .

Be prepared to contact family and support staff.

Via DBSA

When you see major behavioral changes in a student, you need to be prepared to contact parents and bring in professional help. Start by talking with your school counselor, if you have one. Let them know what you’re seeing and ask them to sit in on class for a bit.

If no counselor is available, begin directly with the parents instead. Explain what you’ve observed and how different it is from the student’s usual behavior. See if parents are noticing the same types of things at home. Recommend that the parents take their child for a professional evaluation, starting with their pediatrician.

Let parents know that whether or not the student is diagnosed with childhood depression, you will do all you can to help them succeed in your classroom. Talk about some changes you might make or support you can offer (see below for ideas).

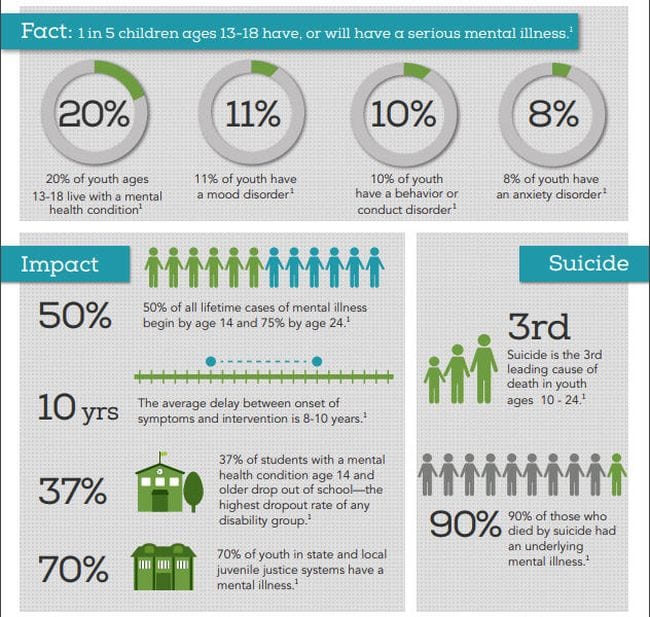

Understand the risk of suicide with childhood depression.

Suicide rates are on the rise in children and teens. Sobering statistics show that kids with untreated depression and anxiety may eventually attempt suicide. If a child in your classroom is talking about killing themselves (even jokingly), looking for ways to die, or saying they have no reason to live, take immediate action. Walk the child directly to the school counselor’s office and tell them what you’ve observed. If no counselor is available, follow your school’s guidelines or call the National Suicide Prevention Line at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Get more detailed information on child and teen suicide here.

Learn how to support a child with depression in the classroom.

Once a child is diagnosed and receiving professional treatment, it takes time for that treatment to be effective. In the meantime, teachers can help kids fight back against their symptoms and be successful in school. Depression may qualify a student for an IEP, but these accommodations can be made with or without formal documentation. (See an in-depth case study of how teachers and schools can help childhood depression here.)

Touch base regularly to discuss progress and establish goals.

Kids with depression often feel scattered, disorganized, and unmotivated. Take concrete action to help them feel in control again. Schedule a formal weekly meeting (Mondays are good) when you and the student can talk about what they accomplished last week and over the weekend and what’s on their plate for the week ahead. For older students with multiple teachers, choose one (or ask the school counselor) to be the touchstone teacher, so the student has one consistent person to talk to and plan with. Try to have an informal check-in most days, too, even just popping by to say hello.

Help the student learn time management and study strategies.

During these weekly meetings, draw up a schedule with school-related timelines, deadlines, and obligations clearly delineated. Teach the student to self-manage their time with checklists and other tools. Encourage them to break bigger projects into much smaller and more manageable parts, so that even on difficult days, they can still make some progress. The Pomodoro Method can be very effective, too.

Accommodate the need for different approaches to learning.

Depression causes fluctuating mood. Some days, the student may have no trouble paying attention in class. Other days, they may find they just can’t concentrate, no matter how hard they try. Give them other ways to absorb the material; allow them to record lectures to listen to later or provide a study guide with important points outlined.

Check in with this student a little more frequently throughout class than you might with other kids. If they seem to have drifted off topic, redirect their attention and provide a small goal they can work to achieve before the bell rings. Consider adjusting deadlines as needed to accommodate difficult days.

Keep all lines of communication open.

The student’s teachers and their family should talk regularly to track progress and share concerns. Send home regular email updates and schedule time to talk with the parents in person or on the phone. Check in with the student’s other teachers consistently to compare notes and provide support. Welcome the child into these conversations whenever possible; let them gain a sense of control over their own life again. If the child is working with a therapist, loop them in from time to time to learn how the strategies they’re working on in therapy can be applied in school too.

Encourage socialization and participation.

As the depression improves, help the student find their way back to doing things they love and spending time with friends. Give them active roles in group projects, invite class participation, and encourage parents to schedule time for social extracurricular activities. Make it easier for them to rejoin the world they left behind when depression invaded their life.

Resources

There’s so much more to know and understand about childhood depression. These resources can help.

Books:

Just a heads up, WeAreTeachers may collect a share of sales from the links on this page. We only recommend items our team loves!

- Depression and Your Child: A Guide for Parents and Caregivers (Serani/2013)

- The Optimistic Child: A Proven Program to Safeguard Children Against Depression and Build Lifelong Resilience (Seligman/2007)

- My Feeling Better Workbook: Help for Kids Who Are Sad and Depressed (Hamil/2008)

Online:

- Depression in Children, Understood.org

- Students Against Depression

- Childhood Depression, Anxiety and Depression Association of America

- Depression in Children, Cleveland Clinic

- Tips for Teachers: Ways to Help Students Who Suffer With Emotions or Behavior, Mental Health America

Teacher depression and anxiety are very common. Learn how others cope and take care of themselves.

Want to talk about helping kids with depression, or your own struggles? Join the WeAreTeachers HELPLINE on Facebook.