Do you want to take your students somewhere amazing next school year? We’ll help you figure out everything you need to know, from field trip fundraising to all of the little details.

1. Research how the trip aligns with and supports your curriculum.

Big trips cost schools money, even if you’re doing field trip fundraising to support most of it. You’re more likely to get your trip approved if you can show your administrator how and why this trip will enhance your curriculum. If you’re feeling really ambitious, write out goals and objectives for your trip, just like you would a lesson plan. The bigger the trip the more this matters.

2. Get permission from your admin.

Once you’ve identified where you want to go, you’ll need to have a talk with your admin. Be prepared. In addition to researching how your trip aligns with curriculum, you’ll want to have a general idea of the cost per student and know what kind of success other teachers have had with similar trips. Be prepared to discuss which adults you want to make the trip with you and how you expect to pay for the trip. Depending on your situation, you may need to be prepared to make a hard sell, or this could just be a formality. Either way, the more questions you are prepared to answer, the happier your admin will be.

3. Decide whether or not to use an agency.

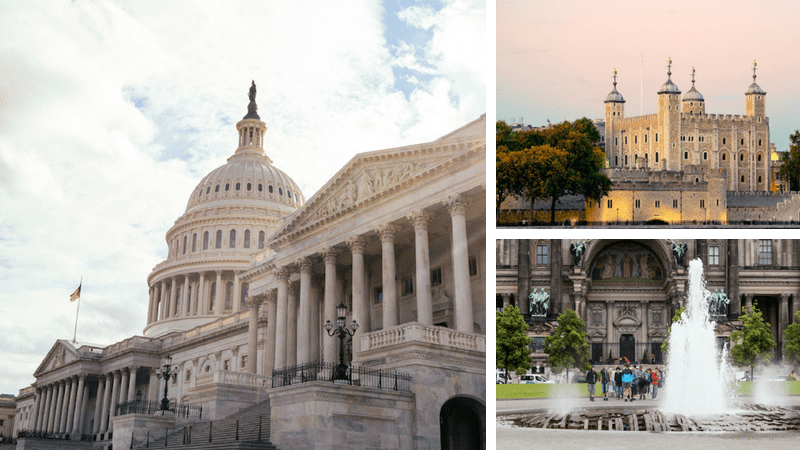

If you’re planning a major trip (cross country, overseas, or someplace more than a few hours away from school), you may want to consider working with an agency. At my school, we book our annual Washington, D.C., trip through an agency. The agency specializes in D.C. trips, and it saves us all sorts of time and stress. I can’t imagine doing this trip without their help. But for our overnight trip to the theatre festival that is a few hours away, teachers handle all of the planning. Since the school organizes this trip every year, most of the details are pretty well ironed out, and the process is smooth. Early in the process, take an honest look at what needs to be done to pull off your trip successfully and determine whether you need to seek outside help.

4. Explore field trip fundraising options.

Most major field trips will cost more than many schools are willing or able to pay for. That usually means that it’s up to teachers and parents to track down field trip fundraising options. There are countless options: bake sales, carnivals, jog-a-thons, and more. One of our favorite field trip fundraising methods is Little Caesars Pizza Kits because they’re such an easy product to sell. Your students’ neighbors may have closets full of wrapping paper, but they are very likely out of pizza. Learn more about how easy it is to run a pizza fundraiser.

5. Have a parent meeting.

The bigger the field trip, the earlier in the year you’ll want to have your parent meeting. Even though both trips are in the spring, we have our Washington, D.C. meeting just after the school year gets underway but hold off on our theatre trip meeting until January. Parent meetings are a great way to set expectations and get a sense of how many chaperones you’re going to have. For big trips, you might even want to hold more than one meeting. Have an initial meeting to introduce the opportunity and gauge interest. (This is also the time to enlist parent support for the field trip fundraising angle.) Then host a follow-up meeting where you review logistics and details.

6. Plan your agenda for the trip.

You’ll want this field trip to be just as well planned as your classroom lessons are, likely even more so. We all know that students with nothing interesting to do will find something interesting to do. So while it may be tempting to loosen the reigns on a field trip, don’t. That’s not to say that you can’t offer your travelers a little autonomy, just make sure you’ve planned that freedom ahead of time and have considered how you are going to make sure students are adequately supervised. Also make sure your students know the plan. Highlight meal times and essential departure times so that you increase the chances of your students being where they should be on time.

7. Investigate flights, hotels, and meal options.

This is one of those tasks that you’ll have to come back to a few times. You’ll want to investigate these costs as you’re requesting permission to hold your event and then again as you begin to make it a reality. Even if you’re not using a travel company for your entire trip, you still may want to consider a travel agent if there is any plane travel involved. Booking flights and hotels for more than a few people can be a logistical nightmare.

Spend some time choosing venues for meals. Maslow’s hierarchy has never been more important than on a major field trip. Kids are going to make better decisions and handle the rest of the uncertainty that comes with travel far better if they are well nourished. Good planning here makes a big difference, especially if you’re traveling with a large group.

8. Arrange for chaperones.

Unless you’re traveling with just a few kids, you’re going to want other adults on this trip with you, and you’ll probably want at least some of those adults to be fellow faculty members. We always have at least one sick child on our annual Washington, D.C., trip, so it’s been important to have some faculty members who can continue the trip with healthy students and some who are willing to stay back when students are ill.

Parents can fill this role, too, but more than a few times we’ve been surprised to find that some of our most supportive parents don’t make the most effective field trip chaperones. Faculty members who know the rules and know the students are often best prepared to engage with students who may be under more stress than usual because of the travel. Which leads to our next piece of advice.

9. Make a plan for student behavior.

We all know that when kids are in new environment they don’t always make the best choices. Set them up for success with crystal clear expectations. Let students know up front what will happen if they aren’t able meet your expectations on the trip. Help them by providing as much information as you can ahead of the trip. For example, “When we visit Arlington National Cemetery on the last day, we will be standing outside for long periods of time. We still expect everyone to show respect by not talking during the wreath ceremony.”

We always hope that students will meet our expectations, but it’s wise to make a plan for students who are simply not able to handle the trip. Will they remain in the hotel room with one of the other chaperones? Will you send them home? (If so, how will they get home? Will you ask their parent to fly out to retrieve them?)

10. Plan your follow-up lessons.

When you provide your students with the kind of schematic context that comes from a major field trip, they are primed for even more learning when they come back. If they’ve visited the Tower of London, for instance, lessons about Henry VIII’s reign will be that much more impactful. Take advantage of this window of opportunity and plan lessons that will let you capitalize on their experience.

Check out our Best Field Trip Ideas for Every Age and Interest (Virtual Options Too!)

What have we missed? Are there things on your must-do list when you’re planning a major field trip? Let us know!