There may be nothing more exciting than watching students engage in a class discussion. When their eyes light up and they walk the tightrope between actively listening to their peers and giving voice to an idea they can’t wait to share, the room just comes alive. But, class-wide discussions don’t always work.

We all know the kids who casually avert their eyes in the hopes of not being called on, just as we know the kids who can’t seem to take a breath long enough to let others find their voice.

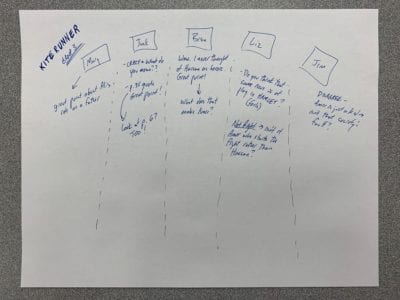

This winter I tried to address these issues by restructuring classroom discussions using a technique called “the fishbowl.” Suddenly, even the most reticent students found they had a voice.

Here is a basic rundown on how fishbowl discussions work.

First, present students with a list of questions to think about.

These questions will be the focus of the discussion.

The questions should be broad and open-ended. As much as possible they should be questions that have more than one possible answer, questions that students can debate rather than answer in short declarative sentences. For English this means questions about theme rather than plot. In science it means questions about systems rather than components. For music it means questions about composition rather than chromatic scales.

By getting the questions ahead of time, every student is empowered to come prepared with something to add to the conversation.

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

Create groups of five or so students.

These are the groups who will enter the “fishbowl” together to talk about their assigned topic while the rest of the class watches them talk.

Here it is important to consider past academic performance as well as personality. I try to create groups that are comprised of a mix of my highest achievers and those who might be struggling a bit, my most reticent speakers and my most talkative kids. This allows the talkative students to work on active listening, while challenging the quiet ones to give voice to their ideas.

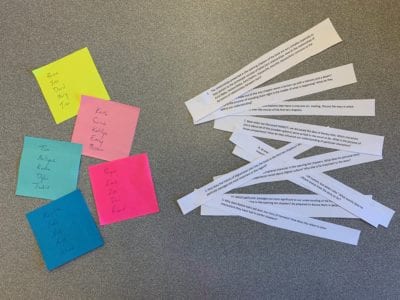

Prepare the system to pick groups on the day of the discussion.

In one pile, place slips of of paper with the groups of five students. In a second pile place the individual questions from the study guide.

On the day of the discussion pull one paper from the pile of groups, and one from list of questions. The group heads to the five hot seats to discuss the question they have been given. The rest of the class watches without saying a word. With the focus on just five students, even the most reluctant speakers rise to the challenge and voice their views.

Instruct the rest of the class to take notes on what they hear.

This is a key element to keeping the class involved while the “focus five” discuss the material.

I tell my students to focus their notes on three things: points people make that they think are particularly interesting or insightful, points they would like clarified, or points they would like to challenge. If you like, the notes each student is taking can be collected and checked for a quick grade. This helps ensure that everyone is staying involved even when it is not their turn to speak.

After a given amount of time, open the conversation to the class.

In my experience, students who have been forced to remain silent during the fishbowl portion are excited to join in.

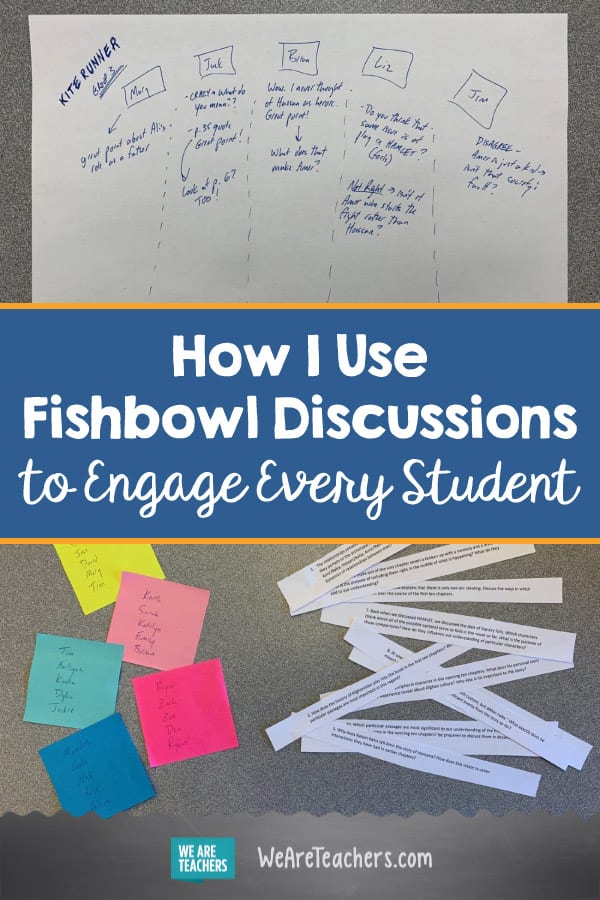

Here they use their notes to praise students for their insights, and offer questions meant to gain more clarity or correct errors. We start with the praise first, making sure each of the “focus five” hears some positive feedback about their contributions. Then we move on to clarifying questions and eventually assertions the class would like to challenge. This is where some of the most interesting discussion happens.

Keep track of each student’s contribution to assess their grade.

The first time I just used a broad tally system—a mark for entering the conversation, a check for making an insightful comment, a question mark for erroneous information. A simple rubric could work as well, perhaps 1-5 scores for contributing regularly, connecting to other’s statements, evidence to support their claims.

Feedback from students has been really positive. “I prepared a lot more for this discussion than for others,” one student wrote. “You said there would be no place to hide, and after watching the first group go I realized you weren’t kidding.” Another student wrote simply, “I had no idea she could talk. She is really freaking smart.”

By the end of a successful fishbowl discussion you will have heard from every student in the room. If all goes well, they will all feel accomplished and engaged, and you will have a clear understanding of who gets it, and who may need a bit more help.

Have you tried fishbowl discussions in your classroom? What was your experience like? Come and share in our WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

Plus, tips for getting students to ask better questions about books.