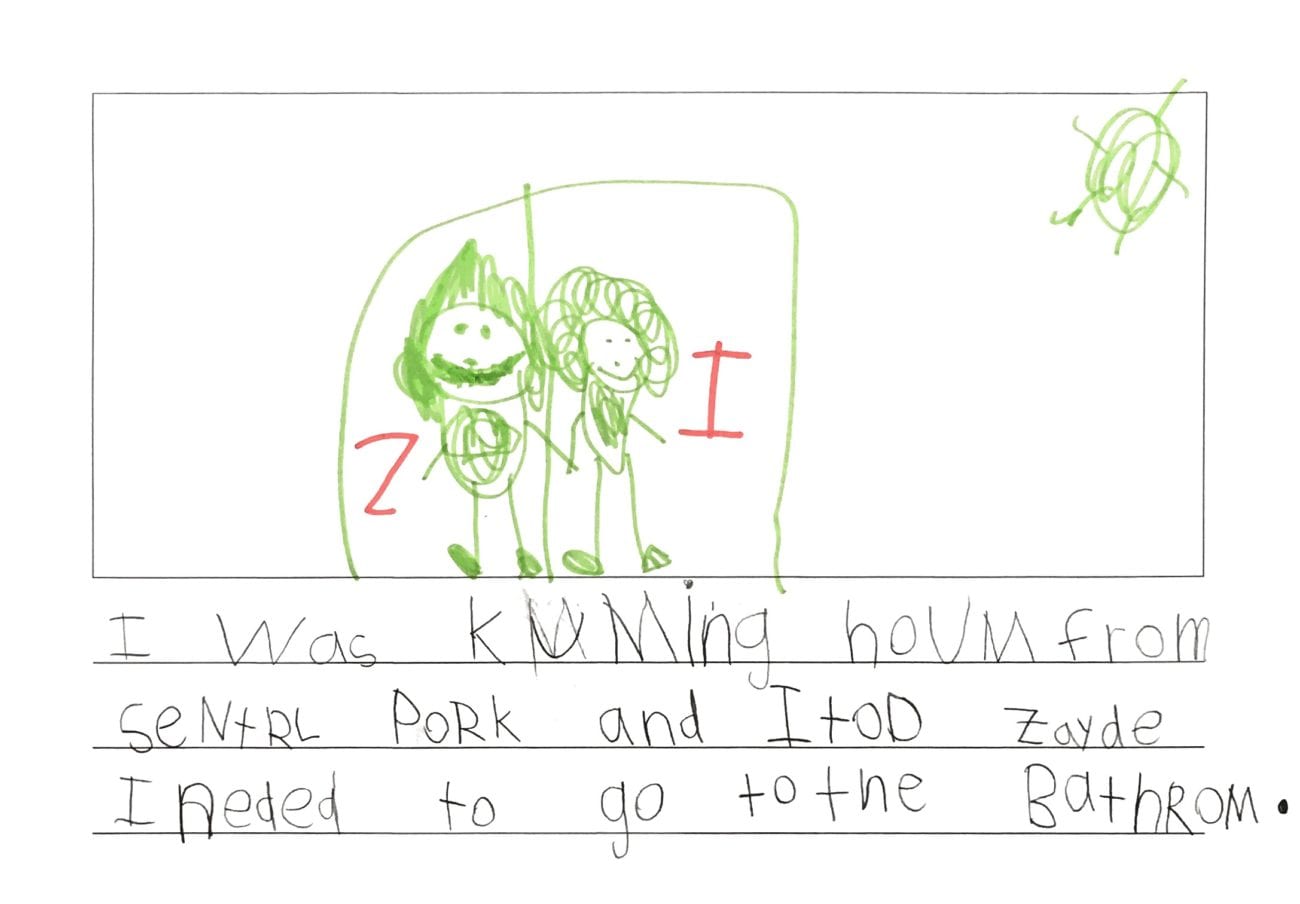

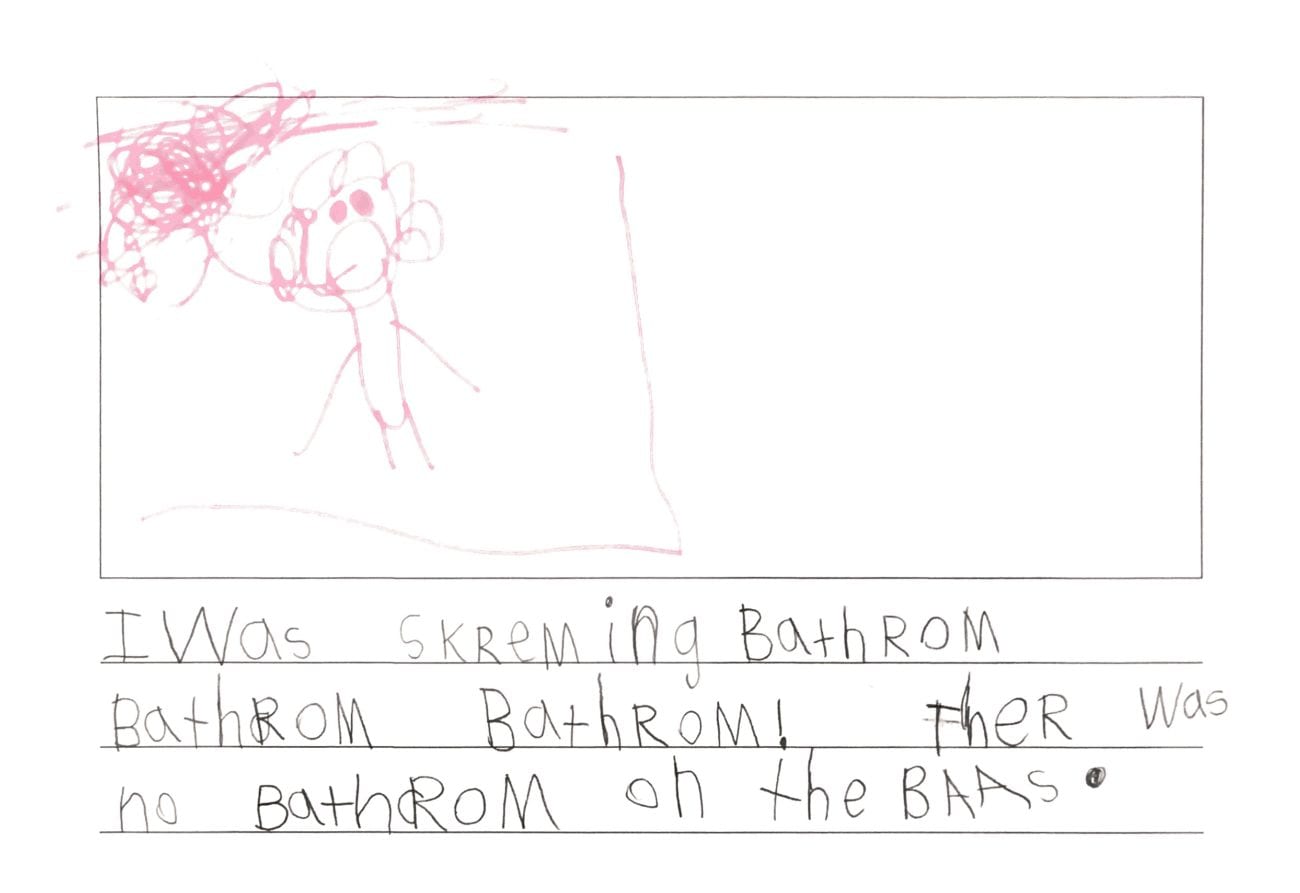

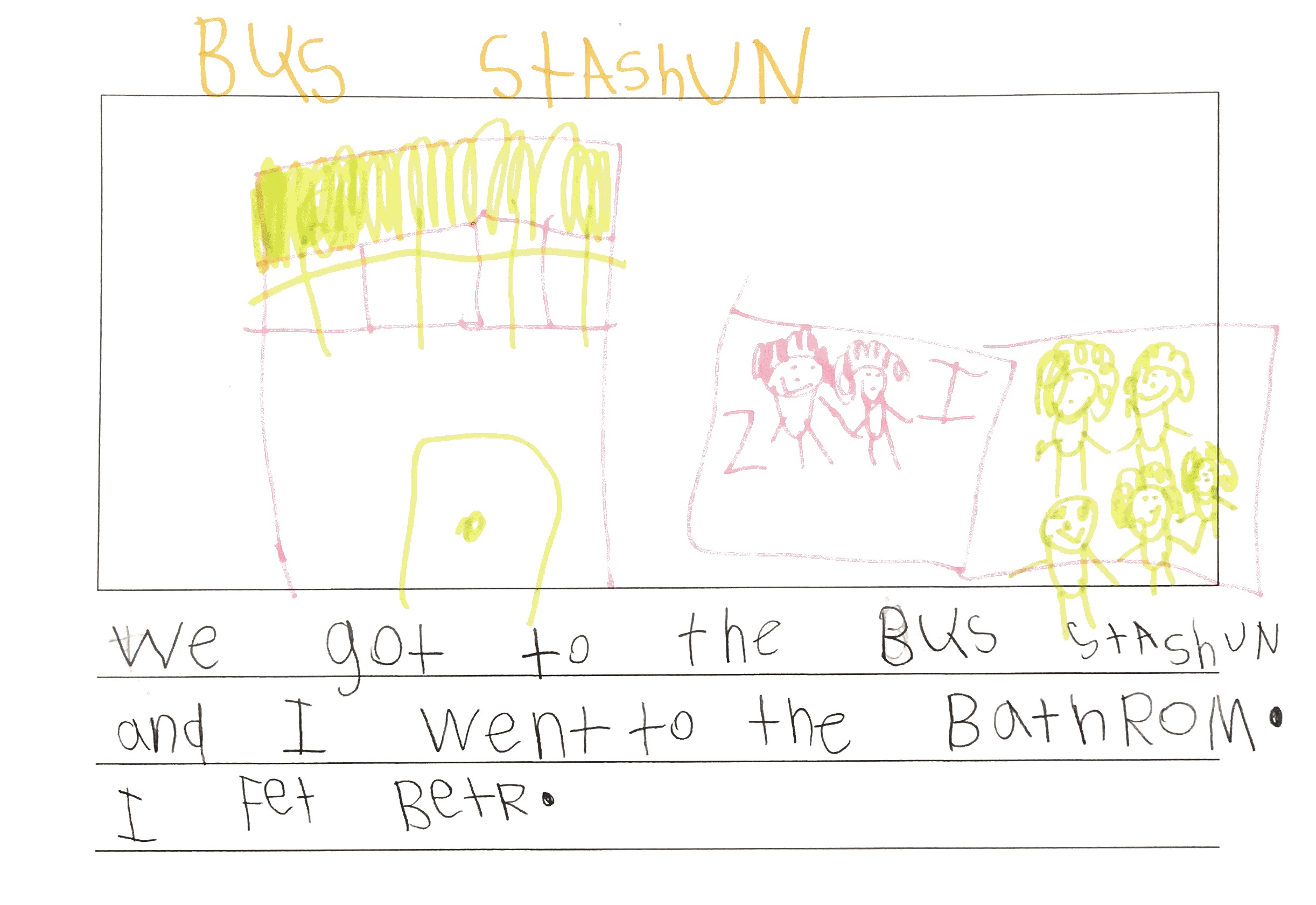

I’m a literacy specialist and the mother of a kindergartner. Therefore, I pay close attention to my daughter’s writing development. In less than a year’s time, I’ve noticed my daughter has evolved from telling a story in pictures to telling a story with pictures and words. As a result, she uses invented spelling with many words when she writes.

The mom in me wants my child to spell words correctly. However, the educator in me realizes she’s taking what she hears in speech and representing it in print. My daughter demonstrates what she knows about letter sounds and phonemic awareness when she invents the spelling of words. While she uses a word wall to help spell the “everywhere words” her class has learned, she makes her best attempt to represent the sounds she hears when she’s spelling everything else on paper.

Invented spelling is an analytical process.

In the early 1970s, a researcher named Charles Read asserted that young children’s attempts at spelling words were not displays of ignorance. Rather, they were windows into each child’s word knowledge. Read coined the term “invented spelling,” which refers to the way a child spells words that aren’t stored in his/her memory phonetically. Earlier this year, Gene Oulette and Monique Sénéchal published a study on invented spelling. In it they state that “Allowing children to engage in the analytical process of invented spelling, followed by appropriate feedback, has been found to facilitate learning to read and spell, not hamper the process.” That’s right, we help students’ future success as readers by giving them the freedom to invent their own spellings when they write.

We need to encourage risk-taking in our young writers.

Encouraging invented spelling allows children to take risks. We must praise emerging writers for their spelling attempts rather than punish them for not getting it right. Remember, invented spelling isn’t an “anything goes” approach. Conversely, it’s a necessary stage to develop the proficiency as a competent and confident writer.

As kids move on through the primary grades, it’s important to teach them the difference between sloppy spelling (i.e., misspelling words they already know) and taking risks to try to spell new or less frequently used words. One way we can do this is by emphasizing using the most accurate spelling possible at all stages of the writing process rather than saving the fixing of spelling errors until they are polishing a piece for publication.

For a short while, invented spelling can be an appropriate strategy.

There is a point at which an invented spelling becomes a permanent misspelling. As children advance in school, we need to be observant about frequently misspelled words in children’s writing. Diane Snowball and Faye Bolton state: “If a child is beyond the phonetic stage of spelling and consistently spells went as whent or they as thay, you probably need to step in, particularly if it is high-frequency words that are being misspelled.” It will take practice and time to master the correct spelling of the word. But eventually, the correct spelling will become automatic.

In The Art of Teaching Writing, second edition, Lucy Calkins posits that “Our students need to realize that it’s okay to make editorial errors as they write; all of us do, and then we correct them as we edit. Although it’s important to teach our students to edit, probably the single most important thing we can do for their syntax, spelling, penmanship, and use of mechanics is to help them write often and with confidence.”

Let’s give our youngest writers the space they need to write with confidence.

Instead of worrying about conventional spelling, let’s praise children for their spelling attempts. There will be plenty of time for them to master conventional spelling in the years to come. For now, let’s put students on a path to success. Allow them to show us what they know about alphabetic knowledge and phonological awareness. Give them the freedom to invent their own spellings.