Teaching strategies come in and out of favor, but ever since I learned about the murder mystery or the murder hunt, it’s been one of my go-to pre-reading activities. I learned about the idea from Paul Ginnis, author of The Teacher’s Toolkit, but have since adapted it to suit my needs. I teach English, but I imagine it could be used in drama, history, or social studies, too.

Here’s how it works:

The idea is simple and can be adapted (oddly!) to texts where there is no murder. The three I regularly use are Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Browning’s “Porphyria’s Lover” and “The Pied Piper of Hamelin.” There are a few steps to creating the activity, but once made it can be used multiple times. Not only that, the students pretty much teach themselves when it’s all set up, so it’s a very easy lesson to facilitate!

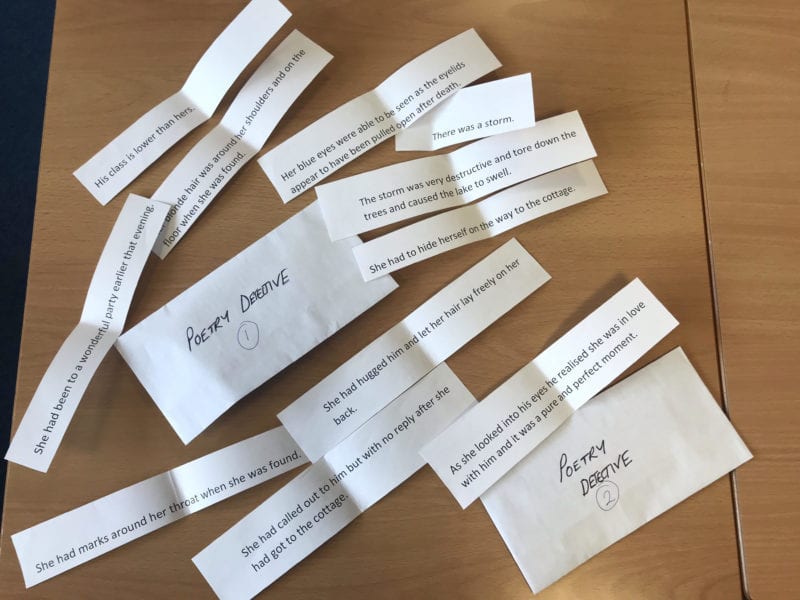

1. Create clue cards.

The first step is to take the story of the text and create a series of clue cards. These are facts about the story. So, for example, here are five cards you might create for Romeo and Juliet:

- Romeo was a Montague

- Juliet was a Capulet

- Two families were fighting

- The apothecary sold Romeo poison

- Juliet’s cousin was murdered

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

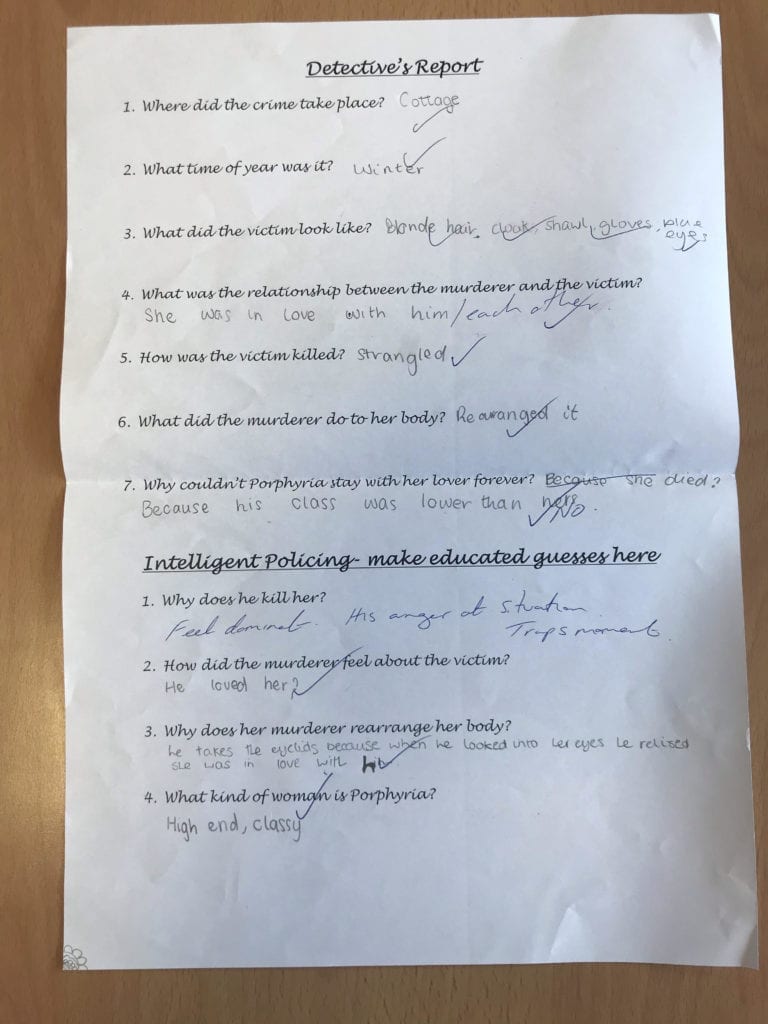

2. Create a detective report.

Once you have all of the clue cards with as many details of the narrative as you want the class to learn, you create a detective report, which the students complete in groups. This is essentially a numbered list of questions or prompts to check their understanding of the facts. This could include questions like:

- Who killed Tybalt?

- Who gave Juliet the sleeping drug?

- Name the two feuding families and their children.

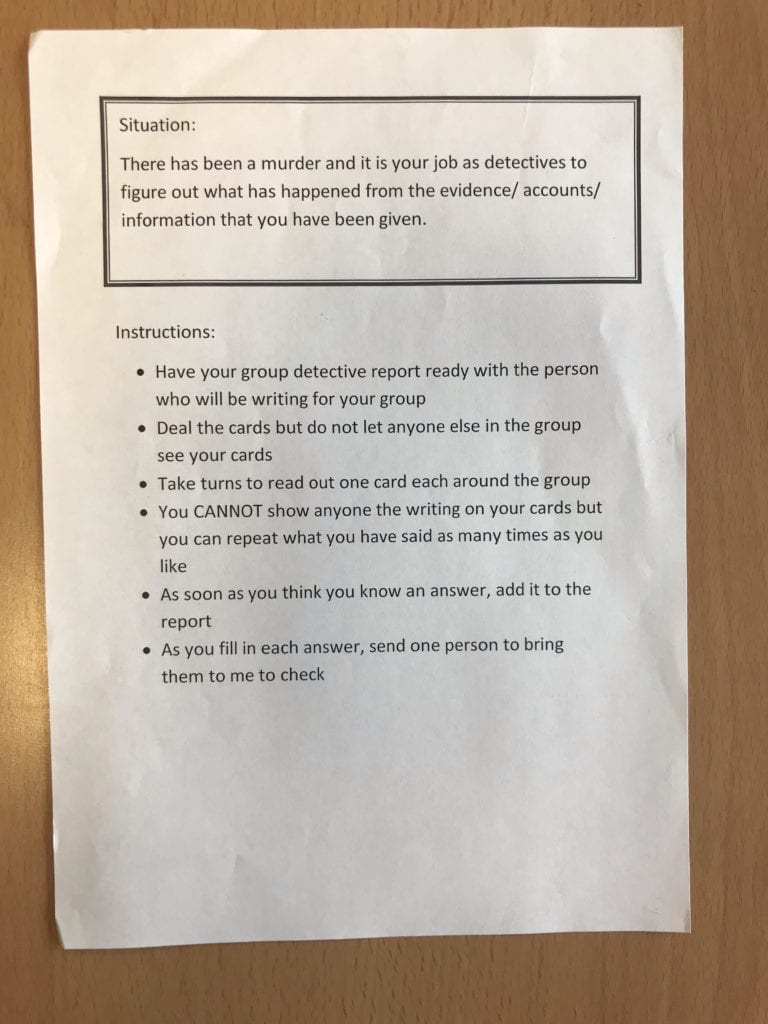

3. Divide students into groups to complete the detective report.

Deal out the clue cards equally between members at the beginning. Students can only read their own cards. They can read them aloud to the group as many times as needed, but they must not show their cards to anyone else. This forces participation and collaboration.

It is a race between groups, and the students must answer the questions in numerical order. This adds pace and challenge. The students must come and have their answers marked as soon as they have answered a question. Here, you are ensuring that each group gets immediate feedback, guidance, or help should they require it. They can only send one person at a time to check the answers with you. It’s too frantic otherwise.

4. Read the text.

Once the students have completed the activity, it’s time to read the text. This is where they really benefit. If it’s Shakespeare, for example, students who would normally struggle to decipher the language really benefit from knowing the plot. If you have used a shorter text, such as a poem, then there are ways to extend the learning, keeping the detective theme.

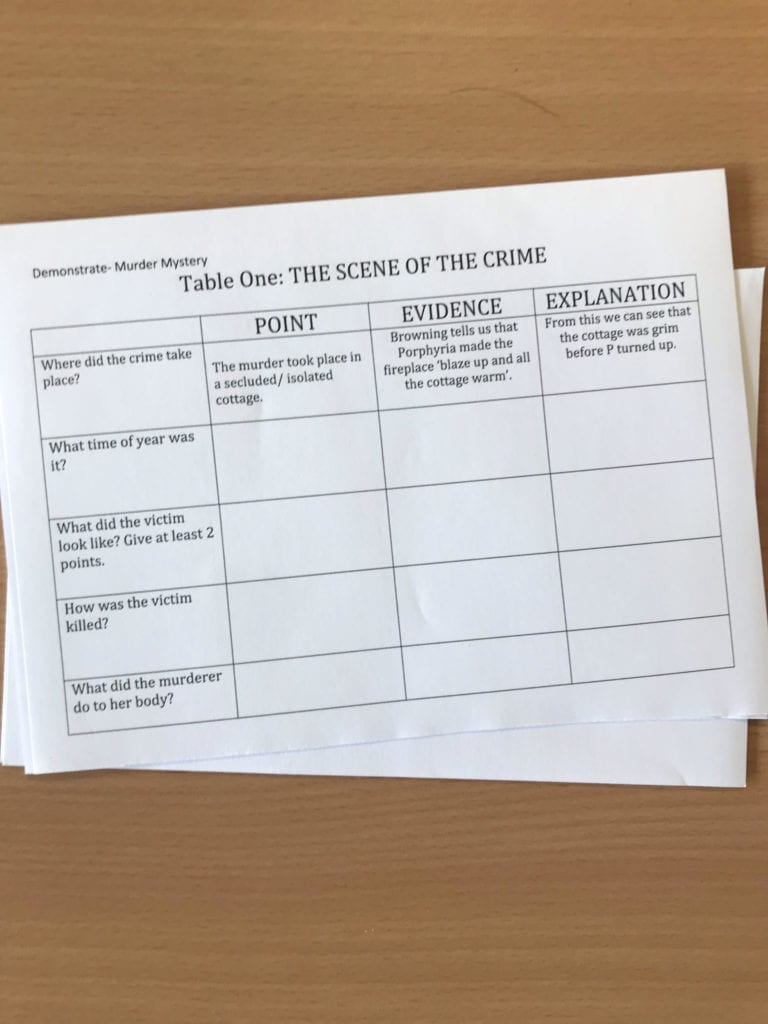

I create a table, which uses the point, evidence, and explanation structure, and have students complete it in the same game format as the murder mystery. They visit me after they complete each row in the table and then deliver the feedback to the group. Maybe they need to integrate the quotation or perhaps add a discourse marker before I will accept the response.

The competition element of both parts really appeals to even the most reluctant learners, and there’s always been such a buzz in the room when I’ve taught this activity. The students tend to retain the information much more successfully than if they were highlighting a synopsis, for example. They have to collaborate successfully if they want to win, and they must negotiate, evaluate, and decide. They peer assess throughout the game and get immediate teacher feedback, which is powerful but difficult to do with big classes. Also, it’s fantastic if you are being observed—it’s a real “wow” once it’s in motion!

Would you try a murder mystery approach to teaching a text? Come and share in our WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

Plus, why I have my students speed-date books.