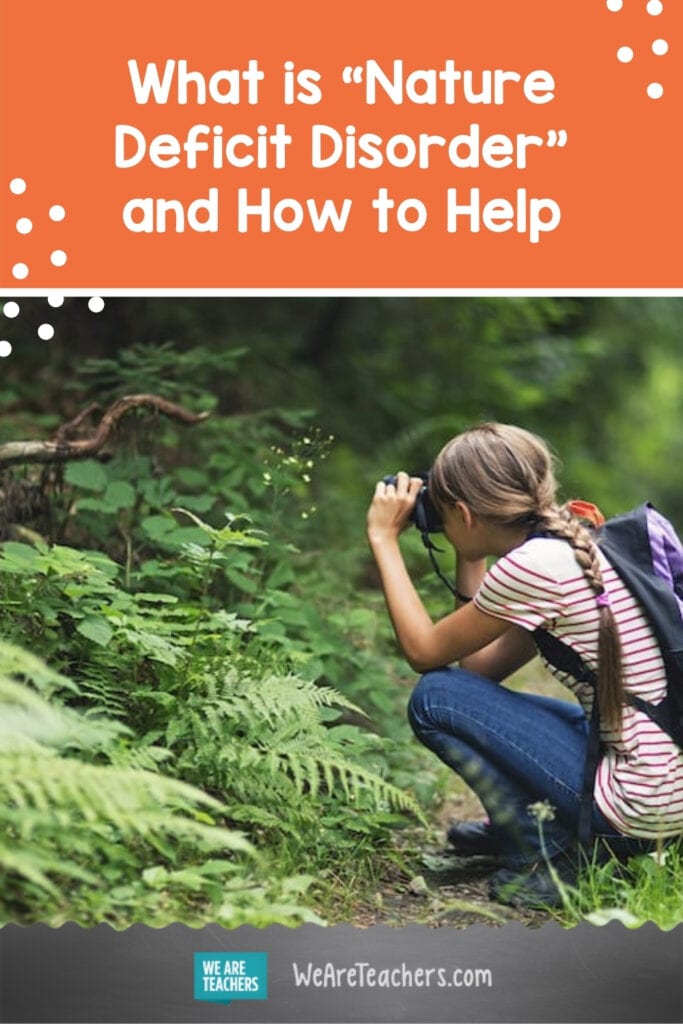

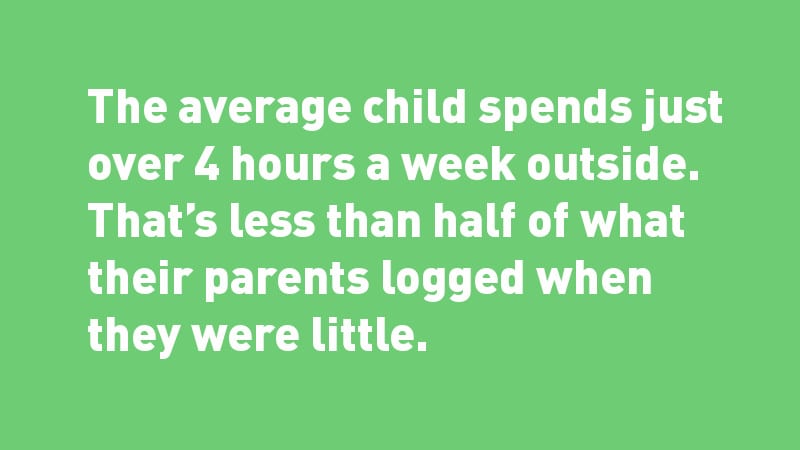

During the last year of coronavirus quarantine, kids spent a LOT of time inside in front of screens. The long months of being cooped up compounded the concern that children are suffering from nature deficit disorder. While it’s not a medical diagnosis, it describes the consequences of spending less time outdoors and becoming disconnected from nature—including diminished use of the senses, attention difficulties, higher rates of obesity, and a host of other physical and emotional illnesses.

Numerous studies have shown the mental and physical benefits of spending time in nature. For children, access to green spaces can decrease stress, aggression, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and boost the immune system. The pandemic reminded us of the importance of spending time outside and connecting with the natural world.

How can teachers—who may be welcoming students back to the classroom, continuing virtual learning, or juggling a combination of the two—help students realize the benefits of time spent in nature?

Recognize that students do not have equal access to green spaces

We can’t take it for granted that children have access to the green spaces that are necessary for their health and well-being. In the United States, access to parks and natural areas reflects broader socioeconomic and racial divides. It’s important to recognize that students face disparities in their access to the outdoors. Provide opportunities and activities that include many different kinds of green spaces, such as walkways, patios, backyards, and urban parks. Connect to groups like Outdoor Afro and Latino Outdoors that promote diversity in outdoor spaces.

Create green spaces on campus

For some students, the school campus might be their best available green space. Plant a vegetable garden or a rain garden (to help collect and purify rain and stormwater) on school grounds. You could also have students plant and maintain a container garden in the classroom. Because watching a plant grow from a seed is pretty darn miraculous.

Take a hike

Plan field trips to parks, wildlife refuges, forests, and wilderness areas within a 60-minute drive from campus. For the cost of a bus ride and sack lunches, you can introduce students to their local natural areas. Lead students on a nature walk or a hike, look for animal tracks or signs, or arrange a scavenger hunt. Consider reaching out to local conservation or environmental education organizations that may have resources to help (including hike leaders).

Bring the outside in

No, this is not an endorsement of wolverines as classroom pets. Too many liability issues. However, this is an endorsement of spying on all kinds of animals and their antics by tuning into live wildlife webcams. For a meditative experience, you can also unwind to the soothing sounds of forests around the world at tree.fm.

Participate in a community science project

Community science (sometimes called “citizen science”) provides opportunities for students to contribute to research on a wide variety of subjects. Students can participate in real science projects that contribute to real scientific conclusions by counting birds, observing night-sky brightness, or observing plant life cycles. Get connected with a local community science project or have students share their observations from the field (even if the field is just their backyard or a neighborhood green space) on iNaturalist.

Encourage close observation with nature journaling

Have students keep a journal throughout the year to record their observations of the natural world. Provide prompts, but don’t be too prescriptive. For example, students might want to express themselves through formal scientific observations, poetry, sketches, prose, or fiction. Have students pick a consistent “sit spot” outdoors where they can sit quietly for 20-30 minutes and record what they see in their journals.

Make homework more outdoorsy

Think about ways to use homework assignments to get kids outside. Write a poem or essay describing something in nature by using the five senses. Create a map (of a local natural area, a neighborhood, or even the school play yard) to encourage exploration. Collect weather data and graph trends over time. Make a collage from items collected outside. Read a book about nature and sit outside to discuss how it relates to students’ experiences.

Welcome and celebrate the different ways students experience nature

Students bring a diverse array of backgrounds, experiences, and expectations to their interactions with nature. Embrace this diversity and encourage students to share the ways they like to spend time outdoors. I took a group of high school students on a trip to an old-growth forest and was horrified when they all got off the bus and immediately whipped out their phones. My instinct was to tell them to put away those confounded devices and behold the majesty (the majesty, dadgummit!) of the forest. But then I realized that they were excited and wanted to record themselves in this new environment and share it with their friends. That kind of excitement is contagious.

There’s no “right” way to experience nature. Nature—with its infinite ways to explore, observe, reflect, play, and connect—has something to offer all of us.

For more content like this, be sure to subscribe to our newsletter!

Plus, How to Help Kids Cope with Climate Change Anxiety.