Unless you’ve been under a rock for the past few years, you’ve likely heard of the “Reading Wars“: the disagreement over the best way to teach children to read. The two sides at odds? Balanced literacy and evidence-based reading instruction, also known as the science of reading.

What’s the difference between balanced literacy and the science of reading?

As the names suggest, these approaches differ in where students should focus skills while learning to read. Where balanced literacy uses a “whole language” approach that focuses on meaning and context, the science of reading focuses on foundational skills like phonemic awareness, phonics, language, and vocabulary. The science of reading differs from balanced literacy in that it emphasizes foundational skills and uses explicit, systematic instruction drawing on research in cognitive science, linguistics, and psychology.

As of April 2024, 38 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws or implemented policies around evidence-based reading instruction. With so many teachers’ previous training being in balanced literacy, we wanted to know how teachers are adjusting to the switch to the science of reading—and where they still need support.

Take a look at our exclusive We Are Teachers survey results and what they say about the state of the science of reading.

We surveyed over 600 teachers who teach kids how to read.

Most of the teachers we surveyed:

- Are elementary public K-5 classroom teachers

- Use science of reading daily or several times a week (84%)

- Say science of reading is most effective when using a mix of small- and large-group instruction (80%)

- Either agree or strongly agree that their school administration supports the implementation of a science of reading approach (78%)

Here’s what they told us.

Most teachers are totally here for the science of reading approach.

When it comes to improving student literacy, most teachers are excited about the shift toward the science of reading approach. According to our survey data, 70% of educators report that this method is either very effective or somewhat effective in the classroom. The results speak for themselves: 90% of teachers whose schools have adopted the science of reading approach have seen measurable improvements in their students’ reading skills since implementation.

However, most teachers say they could use more support.

Despite their enthusiasm for the science of reading, many teachers feel underprepared and overwhelmed. Only 67% say they are very comfortable or comfortable with teaching the science of reading, and a strikingly low 13% feel adequately trained in all areas of this approach. This gap in training leaves many educators struggling to implement the method effectively.

Plus, even with provided curriculum, most teachers are spending their own time finding resources they need to support their students.

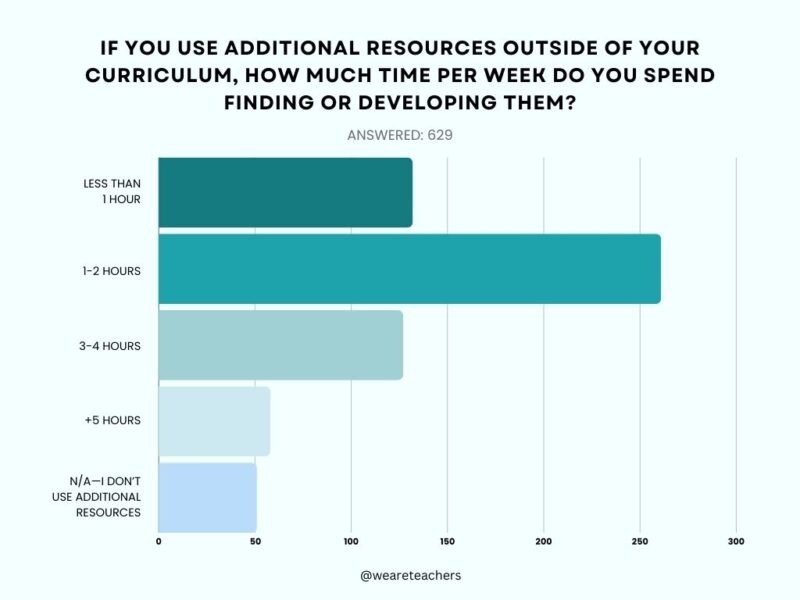

Even with a structured curriculum, teachers are dedicating extra time outside of school hours to find the resources they need to fill in the gaps. According to the survey, 71% of teachers who are teaching science of reading are spending anywhere from 1 to 5+ hours a week searching for materials to supplement their school’s curriculum.

Teachers reported that they could really use more time, materials for differentiation, and adequate classroom support for small groups.

Teachers reported that while the science of reading approach has been effective, they are struggling with the lack of time and resources. Many expressed the need for more materials tailored for differentiation, allowing them to meet the diverse needs of their students. On top of that, they cited a shortage of adequate classroom support for small-group instruction, which is crucial for helping students who need more focused attention.

Other things teachers need: smaller class sizes, better and more frequent training, and parent reinforcement of science of reading strategies.

Beyond time and materials, teachers are calling for structural changes to improve the success of this method. Smaller class sizes would enable them to give more individualized instruction, while better and more frequent training would help them feel confident in using the science of reading approach. Teachers also emphasized the importance of parent reinforcement at home, noting that students benefit when families practice science of reading strategies outside of school.

Still, teachers who have seen a full year or more of the science of reading method are singing its praises.

Despite challenges, teachers who have implemented the science of reading method for a full year or more are overwhelmingly positive about its impact. Many are seeing significant improvements in their students’ reading abilities and believe this approach has the potential to close long-standing literacy gaps. While more support is needed, the results so far have been promising, and teachers are eager to continue using this evidence-based approach.

Here are just a few of the success stories teachers reported:

- Improved spelling and understanding of spelling

- More student awareness of morphology

- Improved literacy in general, impacting growth in other subject areas

- Fewer students needing reading intervention

- Improved student writing

- Emergent readers moving to proficient in the course of a school year

- Especially effective with ELL and SpEd students

One powerful change we could implement? Start training teachers in science of reading earlier.

Our survey shows that teachers are enthusiastic about the science of reading approach and the positive impact it’s having on student literacy. Many have already witnessed measurable improvements in reading skills, reinforcing the effectiveness of this evidence-based method. However, despite their optimism, teachers also highlighted the need for more support. From additional training and classroom resources to more time for lesson planning and smaller class sizes, it’s clear that a curriculum shift on its own is not enough. But maybe with these needs addressed, teachers can more fully realize the potential of this powerful approach to transform literacy education.

Looking for more articles like this? Be sure to subscribe to our newsletters!