If you randomly chose a kindergartner’s backpack and opened it up, you would almost certainly find a mini art gallery.

Sometimes it’s easy to identify the finished product. This red circle speckled with glued-on black dots and a black semicircle head is clearly a ladybug (or a highly suspicious cherry). Other times, it might be a piece of paper with a single crayon mark. To our children, all of it is art.

At my first teaching job, I received explicit instructions on how to manage the art curriculum—namely, don’t.

We were to put materials on a table and let children do anything they wanted with them. No themes or precut shapes, not even to go along with a lesson or at holidays, and we were never to make suggestions, show them how to do something, or praise their work. My supervisor told me this with the same seriousness as someone giving anaphylactic response training. I got the message loud and clear—don’t mess with the art.

I understood the reasoning behind allowing children to explore art unhindered. Certainly unstructured creative expression and the freedom to explore wherever students’ ideas take them is very important in early childhood. Still, was this taking it too far? How would they learn the skills to use during their free creative time? Wouldn’t it be better to teach them varying techniques and then let them apply those techniques how they saw fit?

[contextly_auto_sidebar]

Fortunately, at my next teaching job, I discovered a more balanced approach.

At this center, I met Lisa, an RECE with much more experience than I had. I loved her approach to art and emulated it in my own classrooms. Lisa approached the art curriculum as a hybrid of structured and free creative art. Several times a week, there was a semiguided activity, during which Lisa would sit with the children, show them different techniques, and work with the kids in small groups. For the rest of the day, there was an open creative station containing various art materials, tools, and adhesives for the kids to explore on their own. “When you put it all out and just walk away, it is amazing what they come up with,” says Lisa.

When I spoke with other teacher friends, they echoed this balanced approach in many ways.

Molly King, a former kindergarten teacher in Ontario, provided mostly unstructured art activities but still included some product-oriented projects. “Structured guidelines were given—for example, how to paint without having drips running down [the project],” says Molly. “But the activities were always open-ended in the sense that students chose their own colors and add-ons—which gem stones or decorations they’d like to glue on, and in whatever way they wished, etc.”

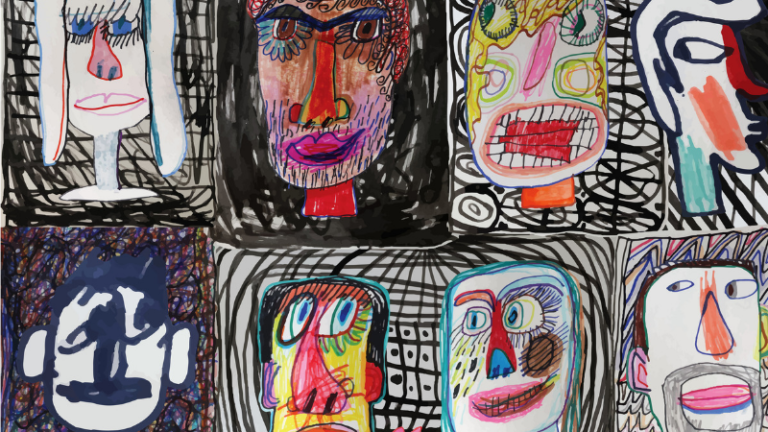

Angela Poll, a teacher at the Peel District School Board in Ontario, prefers to follow the child’s lead when it comes to art. “Some students respond to following steps because drawing or painting, etc. might not be their favorite thing to do, or they haven’t tried it before,” says Angela. Angela also emphasizes the importance of not interpreting children’s art or insisting their art represent the real world, such as suggesting skies be blue. “Imagine if Dali’s art teacher corrected his genius!”

Sarah Mann, a new RECE in Ontario, also tailors the art experience to the child. “All children are different, and some would rather follow instructions and know what to do rather than create spontaneously,” says Sarah. “My answer to that is to always offer a wide variety of choices and to often put out examples.”

Structured art activities do have advantages.

They teach a variety of techniques that children may not stumble upon by themselves. They are a chance to practice following instructions. Not to mention, they can foster a sense of pride at completing a project from start to finish.

But highly structured activities can go beyond stifling creativity.

One study showed that when children were given free range to play and explore without direct supervision, they were more likely to create their own parameters and “think outside the box.” When an adult was present, the children tended to exhibit more expected behaviors in their play, possibly as an attempt to please the adults.

As a teacher, I saw the ways in which we unwittingly contribute to this phenomenon with art.

Overwhelmed by the volume, parents would often tell me to just send home the “good” art. “Good,” for these parents, tended to be defined as art that actually resembled obvious things. Parents usually reacted more positively to the structured art than the free creative art which often appeared random or unfinished to the adult eye.

The children, however, usually valued the opposite. The artwork the kids were most excited to show off were the pieces they’d created themselves, even if to adults it looked like crayon scribbles and a random assortment of feathers. They enjoyed following the steps to make a guided art piece; but they were most excited about the art that was entirely their own. By making a fuss over the more aesthetically pleasing structured pieces and downplaying the free creative ones, we can send the message that the product is more important than the process—or worse, that without help, their creativity doesn’t count as art.

As teachers, we need to give the structure to the kids who want it but give space for children to explore.

Some teachers accomplish this by having both structured and free creative art lessons. Others won’t guide children step by step, but will put out several examples to spark ideas for kids who are overwhelmed at the openness (think of the examples on display at paint-your-own-pottery places). Still other teachers simply sit with the children and make their own art alongside them. “By sitting with them during art activities, I was able to informally demonstrate techniques, like dragging a fork through paint to create texture,” says Molly. “Students could then choose whether or not these were techniques they wanted to attempt themselves.”

All of the teachers I spoke with believe that enjoyment is the main goal of art, regardless of which approach is taken. I believe this, too. It is a sensory experience for little hands; it is a great way for kids to work through the frustrations of the day by funneling their feelings into the manipulation of objects. And it’s simply good, messy fun.

What’s your take on structured art activities versus more open-ended assignments? Come and share in our WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

Plus, 40 ways to make more time for creativity in your classroom.