Post-traumatic stress. That phrase used to make Andrea Fisher, a fourth grade teacher at SENSE Charter School in Indianapolis, Indiana, think about the experiences of soldiers at war—not the experiences of students in her classroom.

The majority of students at SENSE live in poverty, with 97% receiving free or reduced lunch. Fisher knew her students were dealing with stress beyond their years—like whether the electricity would be on when they got home from school or if there would be anything to eat for dinner.

Stressed Brains Don’t Learn as Well

Fisher was inspired to make a difference, but what she didn’t fully realize was how profoundly these chronic stressors at home affected children’s brains while they were in school. No matter how skilled she was at teaching reading, math, or any other subject, it was nearly impossible for her students to succeed—because stressed brains don’t learn as well.

This has become the mantra of SENSE teachers. They’re learning about the impact chronic stress has on their students’ brains through their training and coaching sessions over the past year with Starr Commonwealth. Starr is a nonprofit organization based in Michigan that, among other things, provides schools throughout the United States and Canada with resources to help children who are experiencing trauma.

“Stress makes it impossible for them to process,” explains Emily Hinojosa, a first grade teacher at SENSE. “I could give a direction two or three times, four or five times, and it just does not get through.”

Strong Instruction Doesn’t Always Equal Student Growth

Kristie Sweeney, a 24-year veteran in education and a school leader with experience turning around troubled urban schools, was hired as the principal at SENSE six years ago. Sweeney wanted to know why there were major gaps in student learning even though school evaluations always showed that instruction was very strong.

Sweeney and her team uncovered a staggering statistic: Only 7% of neighborhoods in the nation are more poverty-stricken than the area surrounding SENSE. As they drilled down into the effects of poverty, they realized the reality of childhood trauma at their school. Drug abuse, particularly the opioid epidemic, has viciously affected the community surrounding SENSE, and it is putting undue stress on students by robbing them of the things they need to feel safe, like food, good health, and shelter.

“On any given day, we can see drug deals going down in the parking lot behind us. We can see police officers administering Narcan to bring people back, and our children are going home and finding their parents with needles in their arms, drugs in their homes, strangers coming in and out buying drugs,” Sweeney says. “You also have domestic violence, which our students face on a daily basis as well, and then using money that’s coming in to buy drugs instead of buying food.”

Seeking Out Support

Sweeney and her team knew that at a school with such a large population of students experiencing trauma and a limited team of administrators and school counselors, SENSE needed additional support. So they turned to Starr.

Teachers started completing Starr’s online professional development courses on trauma-informed care, and the school was also assigned a consultant, Derek Allen, a senior trainer with Starr, who visits the school to guide its trauma-informed initiative by assessing progress and offering suggestions for next steps.

Teachers are finding Starr’s training and resources helpful. “It’s not been just listening to or reading things,” says Hinojosa. “It’s been a lot of physical resources and strategies that we’ve been given.”

“SENSE is getting results because they understand that being a trauma-informed school is not just about attending a training, hearing a speaker, or reading a book. To truly be trauma-informed, a school has to change the way they do school. From the approach they take with students who exhibit problematic behavior, to their staffing model, to their job descriptions, to their discipline procedures, to the way they use and adorn physical space. SENSE has and continues to make those adjustments so that all of their students are provided with the positive learning environment they need to flourish.” —Derek Allen

Looking at Behavior through a “Trauma Lens”

A change in mindset is a major part of SENSE’s trauma-informed initiative, especially when it comes to behavior management. Teachers at SENSE are learning how to look at student behavior through a “trauma lens.”

“I think the main thing that I have seen teachers gain, and myself gain, is just our mindset in the way we approach students,” says Erin Good, school counselor at SENSE. “Instead of looking at their behavior and labeling it as lazy, disrespectful, [or] rude, [you’re] reminding yourself that something is happening to that student.”

Fisher pays special attention to her students’ body language and how they speak to her and their peers. She says her students are often set off by seemingly minor occurrences. For example, if a student comes back from the bathroom and slams the classroom door, even if not purposefully, the noise could trigger a classmate to recall a traumatic situation (like when their father slams the door and starts an argument), which causes the classmate to become activated or stressed out, resulting in an emotional outburst in class.

Good says one of the strategies teachers use is asking instead of labeling what is happening to cause the negative behavior they’re seeing from students. When Fisher notices one of her students becoming stressed, she asks questions like, “Hey, how are you today?” “Is everything OK?” “How can I help you?” “Do you want to talk about it?” rather than saying things like, “You’re disrupting my lesson!” or “Why did you throw your pencil?”

Creating a Calm-Down Spot

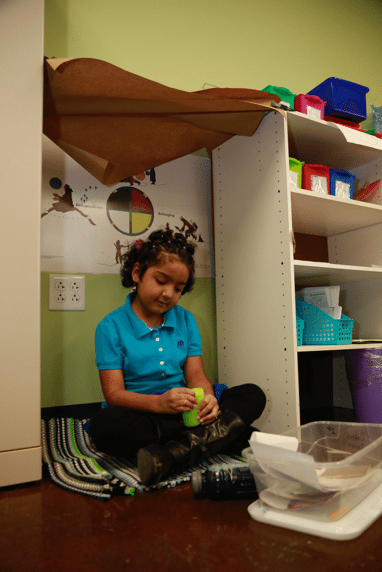

If a child is showing signs of escalating behavior, teachers at SENSE often help their students get in the right mindset to learn by offering them an opportunity to spend time in the classroom’s Calm-Down Spot. In Hinojosa’s first grade classroom, this area looks like a cozy, makeshift tent created out of butcher-block paper. In Fisher’s fourth grade classroom, it’s a desk in a private area between two filing cabinets decorated with motivational posters.

Every Calm-Down Spot has one thing in common: a Coping Skills Box, which contains various comfort items such as a squeeze noodle (a slice of a cut-up pool noodle); a visual for relaxing breathing exercises (for younger students); a diagram of positive visualization techniques (for older students); and a mind jar (a water bottle filled with glitter and food coloring).

Going to the Calm-Down Spot isn’t punitive, like standing in the corner or going to “timeout.” Instead it’s a quiet place where students can choose to go when they need time to cope with stress and reset their behavior before returning to the main classroom to learn.

A student in Hinojosa’s class who was dealing with a lot of challenges at home, like whether she’d have a bed to sleep in or food to eat, was also having a difficult time in class. She would roll around on the floor and shout out over her classmates and teachers. So Hinojosa and her co-teacher offered the student breaks in the Calm-Down Spot.

“I could tell that she just had a lot in her brain, and it just came out in whatever way it could,” says Hinojosa. “We first started with if you’re having trouble controlling your body, if you’re having trouble controlling your mouth, you can always take a break.”

The teachers even incorporated writing, an activity the student enjoys, into the Calm-Down Spot, and encouraged the student to write letters to the school counselor.

Trading in Clip Charts for Courage

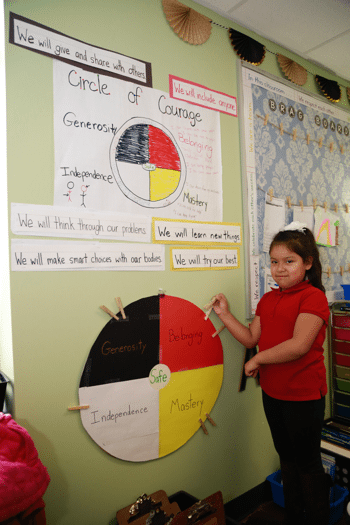

One of the biggest changes for the students at SENSE has been the elimination of behavior point systems and clip charts. Teachers are replacing them with a model called the Circle of Courage, which is based on the idea that to be emotionally healthy, all children need a sense of belonging, mastery, independence, and generosity.

SENSE incorporates the Circle of Courage throughout the day in everything from morning announcements to behavior management in the classroom. “When we see a student doing something great, we reference the Circle of Courage, says Fisher. “When we see a student that needs to be redirected, we reference the Circle of Courage.”

The new model seems to be making an impact on the students, who are now excited to talk about repairing broken circles with kindness and acceptance.

“The Circle of Courage is about friends [and] your heart,” says Maria de Jesus Garcia, a first grader in Hinojosa’s class. “If someone breaks it, your circle feels bad, and when somebody does something kind, your circle gets better and goes to a happy place.”

First grader Elijah Malachi Donegan adds, “I was proud that I straightened someone’s circle because they fell down, and I asked if they were OK.”

The Circle of Courage has also changed the way SENSE teachers use Class Dojo, a behavior system where students earn or lose points. After a recent coaching session with Allen, fourth grade teachers realized the points were creating unhealthy competition in their classrooms and decided to stop using them. Now, Fisher meets with her students individually each week to talk about which parts of the Circle of Courage they’ve done well and sets goals for the parts they want to improve.

Student Success Room: An In-School Suspension Alternative

Another major change SENSE made, at the recommendation of Starr, is replacing the In-School Suspension Room with the Student Success Room. The room is staffed with a full-time social worker, whose role is to help students learn coping skills and mediate conflicts.

The room looks like a sensory wonderland. It includes different stations, such as a corner with plush pillows and stuffed animals to cuddle; a yoga area with mats and a balance ball; a table with crayons and mindfulness coloring books; an area to create sculptures with kinetic sand; and a full-size hammock for relaxation.

While the Student Success Room seems like a fun place to play, the purpose is much deeper. When there’s a conflict in the classroom, whether it’s student-to-student or student-to-teacher, children can relax in the room for a few minutes and use the therapeutic tools. Once they calm down, students talk with the Student Success Room coordinator about what happened. If it’s a student-to-teacher conflict, the teacher comes to the room to mediate with the student. The goal is to repair relationships so teachers are accepting of students coming back to the classroom and students are accepting of working collaboratively with teachers again. It also gives teachers an opportunity to let students know they care about them and want them to succeed.

Self-Care for Teachers

In a school like SENSE, students aren’t the only ones who need support to be successful. Hardworking teachers can burn out or even suffer from compassion fatigue when working with (and worrying about) their students both inside and outside the classroom. That’s why teacher self-care is another important aspect of a trauma-informed school.

Hinojosa and Fisher both say they like to decompress by turning up the radio and listening to their favorite music as they drive home from work. They try their best to leave their stress at school and focus on themselves and their families after they leave for the day.

“When I’m driving away, I can turn the radio on, and I can say, ‘Now I’m going to think about me. I’m going to think about my family. I’m going to think about my pets,’” says Hinojosa. “So that I can make sure that my own personal self is capable of dealing with whatever the next day is going to bring.”