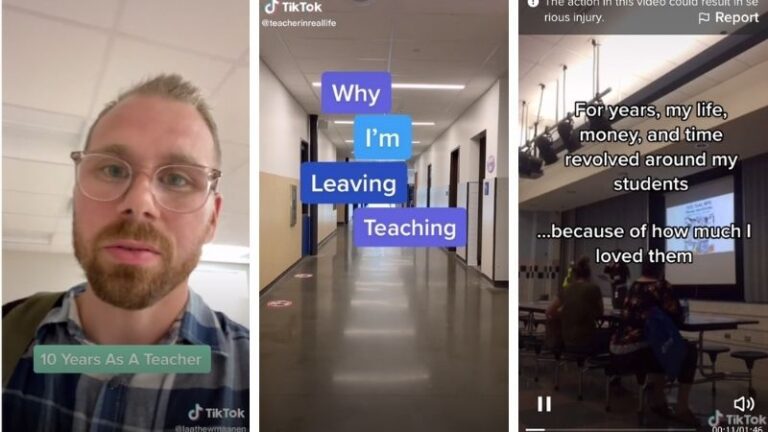

You’ve seen the viral resignation letters. Committed teachers who quit—in very public fashion—create a stir that ripples across communities and comments sections. But what happens to the teachers? After the publicity dies down, and they’re out of a job they once loved—what then?

We tracked down four teachers whose resignations went viral. Here’s what they have to say, in their own words.

Anne Marie Corgill

Resigned in: 2015

Currently: Teaches first grade in Hoover, AL

On teaching: “Bravery is not always easy, but it’s necessary.”

Read her resignation letter

“In order to attract and retain the best teachers, we must feel trusted, valued, and treated as professionals.”

Corgill was Alabama’s 2014-2015 Teacher of the Year and a 2015 National Teacher of the Year finalist. But when the state of Alabama called her “unqualified” to teach fifth grade, she resigned rather than “paying more fees, taking more tests and proving once again that I am qualified to teach.”

The apparently abrupt resignation of an award-winning teacher was Internet gold, and her resignation letter—which she says was leaked to the press without her knowledge—spurred “so many rumors,” she says. Few commenters, though, understood the complex bureaucratic nightmare that led to Corgill’s resignation.

The veteran teacher holds Alabama Department of Education Class A and B certifications to teach primary school through third grade students, a New York teaching license for elementary school through grade six and National Board Certification to teach children ages 7 through 12. Yet within a month of transferring to a fifth grade classroom at the request of her principal, Corgill was contacted by the Alabama Department of Education and informed that she would need additional certifications to teach fifth grade.

“That was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” Corgill says. “It was time for me to say this is not okay. It’s not okay for teachers to be treated in this manner. Don’t tell me you want National Board teachers in every classroom, and then you don’t value the certificates that they gain.”

Corgill spent the next year creating a business plan for a new type of school, one that would meld teacher education with elementary education. “My vision is a two-story building, with the school of education above an elementary school,” Corgill says. Teacher trainees would job shadow experienced teachers from the very beginning of their education, and continue to work in classrooms throughout their education.

Today, Corgill is back in the classroom and “loving being back with kids.”

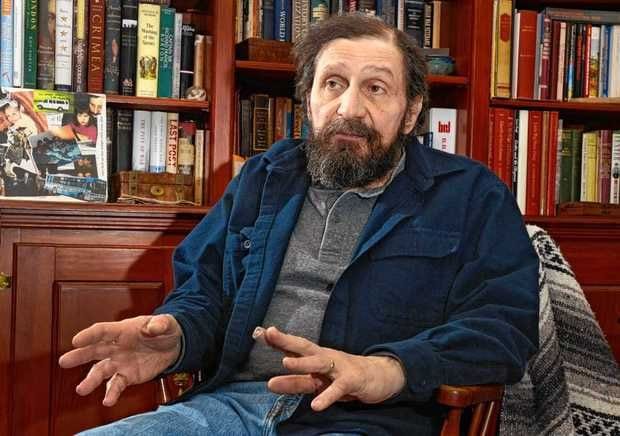

Jerry Conti

Resigned in: 2013

Currently: Retired

On teaching: “One of the things I’m proudest of is that I produced a hell of a lot of teachers.”

Read his resignation letter

“Creativity, academic freedom, teacher autonomy, experimentation, and innovation are being stifled in a misguided effort to fix what isn’t broken.”

Frustrated by an ever-increasing focus on testing and teacher accountability, Conti resigned rather than continue to teach in a system that no longer supported the best interests of teacher or students.

Conti, a 40-year teaching veteran, stepped down from his post as a high school history teacher at Westhill High School in Syracuse, NY in 2013, but he hasn’t stopped teaching. He stays in touch with hundreds of his former students via Facebook, many of whom now teach history and social studies at schools throughout the nation. “They still contact me and ask for advice,” Conti says. “I’ll give them some ideas of what I did in the past and have them try it and see if it works.”

If educational trends had gone in another direction, it’s likely that Conti would still be in the classroom. But “the bureaucracy,” he says, “had gotten to the point of ridiculousness. Testing became more important than teaching, and you can’t test your way to nirvana.”

Increased, often nonsensical demands on teachers haven’t helped, he says. “I needed more time to be creative and more time with my kids,” Conti says. “I didn’t need more time sitting in endless meetings or filling out paperwork. It was a game I couldn’t play anymore.”

Pauline Hawkins

Resigned in: 2014

Currently: Adjunct professor at a community college; author of Uncommon Core: 25 Ways to Help Your Child Succeed in a Cookie Cutter Educational System

On teaching: “We need to start working together to do what’s right for our kids.”

Read her resignation letter

“I can no longer be a part of a system that continues to do the exact opposite of what I am supposed to do as a teacher.”

For Hawkins, teaching is more than a job; it’s a calling.

“From my first day of teaching, I knew how to make a connection with my students and engage the reluctant learner,” she says. “I taught high school for 11 years and absolutely loved it.”

Like most successful teachers, Hawkins emphasized connection over curriculum. But over time, “with the legislation, especially with Race to the Top and Common Core, it became all about the curriculum,” she says. “The curriculum was the magic pixie dust that was going to make these kids successful.”

The decision to leave the classroom was “heartbreaking,” Hawkins says. And though she’s currently teaching at the college level, “it’s not the same,” she says. “It’s not really what I feel called to do.” So she continues to advocate for teachers and for common sense, connection and compassion over curriculum.

“I’m still fighting; I’m just fighting from a different place,” she says. “I’m writing more. I’m posting things online. I’m advocating for my son. We have so many brilliant teachers here that if we would just let the teachers be in charge, we would fix everything.”

Tracey Suits

Resigned in: 2016

Currently: A librarian with the Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library

On teaching: “Money isn’t everything. Your health is more important.”

Read her resignation letter

“I cannot continue to teach students to regurgitate information for secretive, high-stakes, standardized tests when it goes against everything I morally stand for.”

When her health started to suffer—when she was crying in her car before school and experiencing anxiety attacks and flare-ups of her auto-immune disorder—Suits knew something had to give. So the school media specialist resigned, took a big pay cut and accepted a position as a librarian.

“I went from the most stressful position to one of the least,” Suits says. “When I first started at the library, I was working the reference phone line, and people were so appreciative—thank you very much and wow, I don’t know what we would do without you and I’m glad you helped me. Teachers don’t hear that. They don’t hear it from their students and they definitely don’t hear it from the parents.”

Few people in the general public, Suits says, fully understand the stress and strain on teachers. Yet teachers are often reluctant to share on-the-ground reality, for obvious reasons.

“There are so many teachers now on annual contracts; the word ‘tenure’ has almost gotten to be a bad word. So teachers are afraid that if they speak out, they’ll be given horrible classes next year or will be somehow penalized,” Suits says. “That’s a real shame.”

Suits is doing what she can to help from outside the system. “I recently set up a card table outside our public library and asked people to sign a petition to let the superintendent know that teachers need a raise,” she says. “Teachers don’t have the time to do that, so I’m advocating for them now.”