Providing students with better instructional scaffolding is often a school-wide objective, but how can teachers put this big idea into practice? Here are some teacher-tested tips and scaffolding examples to try in your own classroom.

Jump to:

What is scaffolding in education?

Explicit Instruction in Instructional Scaffolding

Instructional Scaffolding Examples and Strategies

What is scaffolding in education?

Imagine you’ve been tasked with building a skyscraper from the ground up. If you’re not an architect, engineer, or construction expert, chances are you’d have no idea where to start. Even if you did have some expertise, you’d still need to tackle such an enormous project in stages.

Each part of the project requires its own specialized tools and materials, and the entire project builds on itself as it progresses. You can’t build the penthouse before digging the foundation! Along the way, workers build many temporary structures to support the ongoing construction, removing them as each new stage is complete.

Teachers can approach big concepts or complex skills just like building a skyscraper, using a technique known as instructional scaffolding. This involves breaking learning into manageable chunks and supporting students as they progress toward stronger understanding and ultimately greater independence. Over time, they no longer need as much support and eventually are able to handle the skill or concept all on their own.

One classic scaffolding example is the way we teach children to read. We don’t thrust books into their hands and immediately expect them to read the words on the page. Instead, we build a variety of skills over time, like knowing the alphabet, letter-sound correspondence, phonics concepts, sight words, and more.

We assist kids along the learning journey, developing and assembling their reading skills over several years. Eventually, we can remove the instructional scaffolding supports and watch kids read independently and confidently!

Learn much more about instructional scaffolding here.

Explicit Instruction in Instructional Scaffolding

One key to educational scaffolding is systematic explicit instruction. In this type of learning, the teacher presents important information up front, then models the skill or concept for students. Students are given a chance to practice themselves, first guided by the teacher and then independently. This modeling and guidance is the “scaffolding” that supports them as they learn.

Throughout explicit instruction, teachers must provide immediate corrective feedback. Catching students’ errors while they’re still practicing will prevent them from learning the skill incorrectly and then continuing to practice it incorrectly during homework and other assignments.

Explicit instruction contrasts with methods like project-based learning, play-based learning, or inquiry-based learning. Instead of allowing students to discover information on their own, explicit instruction presents the information up front, with the teacher demonstrating and modeling the desired skill or behavior. Below, you’ll find reliable scaffolding examples to try with your students.

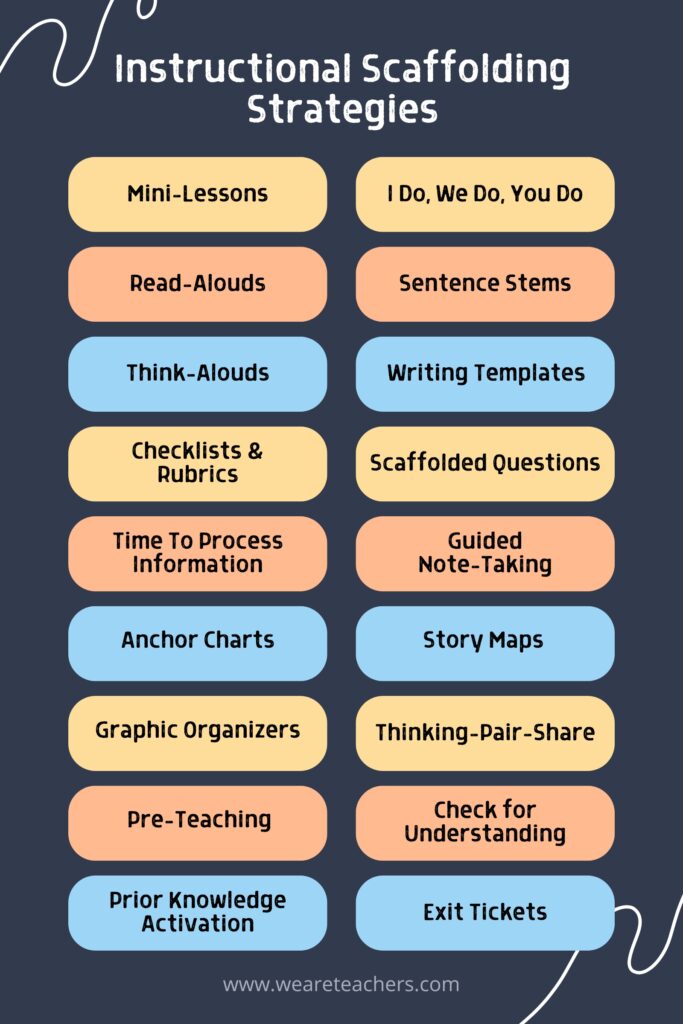

Instructional Scaffolding Examples and Strategies

1. Mini-Lessons

Mini-lessons, lasting only 10-15 minutes each, concentrate on one specific skill or concept at a time. It ensures every student has a chance to digest and master that skill or concept before they move on. Teaching a series of mini-lessons provides students with a safety net that moves them progressively toward deeper understanding.

Create a mini-lesson in much the same way you’d create a standard lesson, but keep the learning goal focused on one specific skill or concept. Introduce the topic and explain the key information. Give students a chance to apply the information in guided practice, then a chance to practice on their own. This builds confidence and establishes a foundation for what comes next.

Try it: Ways To Do Writing Mini-Lessons Using Your Interactive Projector

2. Read-Alouds

Learning to read is about more than sounding out words. To be a truly fluent reader, a student must be able to read out loud smoothly and at a conversational pace, using expression that suits the text. When we read aloud to kids, we’re modeling that fluent behavior for them to practice, making story time an excellent scaffolding example.

Try it: Reading Fluency Is About Accuracy, Expression, and Phrasing—Not Just Speed

3. Think-Alouds

You can demonstrate skills, of course, but how do you model thinking for kids? By doing it aloud! This gives your students a model for their own inner dialogue as they learn.

Teachers already do this frequently as they demonstrate the way to solve a math equation or complete a science experiment. But you can use it with every subject and topic. For instance, as you read a book out loud to your students, stop along the way and share what you’re thinking about the characters and events. Ask them to contribute their own thoughts too. This models reading comprehension and analysis for your students, and it gives them a chance to practice too.

Try it: Improve Reading Comprehension With Think-Alouds

4. Checklists and Rubrics

Some students struggle to remember all the steps they have to follow for a big project or assignment. Scaffold learning by breaking down directions into chunks that students can complete one step at a time, and give them a checklist that they can follow. By breaking it down, you’re providing scaffolds that many students need. Eventually, they can use this strategy on their own to plan and manage their own projects.

Scoring rubrics are another scaffolding example: They guide students through the requirements to achieve their desired outcome or grade on a project. By providing clear and specific examples, you help kids know what they need to do to succeed.

Try it: Helpful Scoring Rubric Examples for All Grades

5. Time To Process Information

Here’s some great advice from elementary teacher Tammy DeShaw: “We move so fast as teachers because we fear that we won’t get through it all,” she says. “But when we slow down and give students more time to process, we are really helping students.”

She continues, “It’s an effective scaffolding strategy when we pause at various points of instruction and break it up. Think about it. If something is above your head, it’s immediately overwhelming. But if you break it into manageable chunks and take your time through it, you’re able to process it much better!”

6. Anchor Charts

These are a common classroom tool, and they’re terrific for scaffolding learning. As you teach, you build the anchor chart together with students. Then, you keep it posted where they can refer to it during their hands-on practice time. It serves as a support until they’ve internalized the information and feel confident completing a task with that particular support tool.

Try it: Anchor Charts 101: Why and How To Use Them

7. Graphic Organizers

A graphic organizer is a powerful visual learning tool that teachers can use to help students organize their thinking before, during, or after a lesson. They provide scaffolded support as students work on the skills or knowledge independently, just like an anchor chart.

Try it: Graphic Organizers 101

8. Pre-Teaching

Build necessary background knowledge by pre-teaching important information before you tackle a bigger concept. For instance, teach important vocabulary words about living cells before you explore the details of how cells work. Before you start a lesson on the American Revolution, ensure students have background knowledge on the figures and political issues involved. Ready to begin a new novel in literature class? Spend some time learning about the time and place the novel is set in first.

9. Prior Knowledge Activation

Pre-teaching isn’t always necessary—sometimes students already have the knowledge they need. However, that doesn’t mean they can immediately bring it to mind. So before you begin a new concept, identify important background knowledge students already have, and take some time to review it together.

Try it: What Is Background Knowledge? (Plus 21 Ways To Build It)

10. I Do, We Do, You Do

The goal of scaffolding instruction is to build confidence so students can learn to do a task or recall knowledge on their own. Try this method:

I Do: The teacher demonstrates or models the skill or concept for students.

- Example: “For many nouns, we can make them plural by just adding an s. For example, ‘pig’ becomes ‘pigs’ and ‘book’ becomes ‘books.’” [Teacher writes words on the board as they talk.]

We Do: The teacher works together with students to practice the skill or concept.

- Example: “Let’s try one together. How do you spell the word ‘cup’?” [Class responds C-U-P and teacher writes letters on the board.] “How do we make this word plural?” [Class says “add s to the end. Teacher writes the s at the end of the word.”

You Do: Students practice the skill or concept independently.

- Example: “Here’s a list of 10 singular nouns. Write each one on your own piece of paper, making them plural.” [Students work on their own or in groups; teacher circulates and offers corrections as needed.]

11. Sentence Stems

Give students a head start during the guided practice portion of your scaffolded instruction with sentence stems. Provide students with the first part of a statement and ask them to fill in the blanks. Sentence starters can be an especially great support for English-language learners.

Try it: Sentence Stems: How To Use Them Plus Examples for Every Subject

12. Writing Templates

If you’re teaching students creative writing or how to write essays, use templates as part of scaffolded instruction. These will guide your students through the process of writing a specific type of poem, crafting an essay outline, or laying out a narrative arc for a story. Eventually, they’ll be able to write on their own, without needing a template as a guide.

Try it: Free Printable Haiku Starter Worksheets

13. Scaffolded Questions

Both lower-order thinking (remember, understand, and apply) and higher-order thinking (analyze, evaluate, and create) are important parts of learning. Generally, we start out by asking students lower-order thinking questions like “Who is the protagonist?” or “When did this battle happen?” Then, we progress to higher-order options like “Did this character make the right decision?” or “What would have happened if the other side won the battle?” This guides students to a deeper understanding of a topic.

Try it: 70 Lower- and Higher-Order Thinking Questions and Sentence Stems

14. Guided Note-Taking

Learning to take good notes is a valuable skill, but it doesn’t come naturally to many students. Teachers can help them learn the process as well as ensuring they learn what they need to know on a given topic with guided note-taking. Some ideas:

- Provide a basic outline students can fill in as you go along, and help them complete it correctly.

- Teach a more complex system like the Cornell Method by having students copy pre-written notes directly into their own notebooks.

- Create a mind map together as a class, then share it with students in Google Classroom so they can save it to their own notes.

- Ask each student to create their own sketch notes, then make copies and share them with other students so they’ll get inspiration as well as study aids.

Try it: 11 Helpful Note-Taking Strategies Your Students Should Know

15. Story Maps

This specific type of graphic organizer helps students understand novels more fully and deeply. It provides places to make notes on:

- Setting and background info

- Character traits and development

- Narrative plot arc events

- Problems/conflicts and solutions

- Main ideas/themes

They can use these notes to prepare for tests or write a report or essay. They’re also very helpful during classroom discussions and debates.

16. Think-Pair-Share

Participating in classroom discussions is difficult for many students. They often benefit from a chance to think their answers through, then discuss them in a pair or small group before presenting their ideas to the class in general. Think-pair-share is one of those smart scaffolding examples that helps build confidence in students and makes them more willing to join in the conversation as time goes by.

Try it: Think-Pair-Share and 10 Fun Variations

17. Check for Understanding

Since you’re purposely building skills or concepts a bit at a time, it’s important to have a good idea along the way of whether your students are catching on and getting it right. That means keeping a close eye on them while they learn and practice, and correcting errors right away when you see them.

Try it: 20 Creative Ways To Check for Understanding

18. Exit Tickets

One of our favorite scaffolding examples is exit tickets, a popular formative assessment used to check for understanding. At the end of a lesson or class period, students complete these tickets and hand them in on their way out the door. On the ticket, they respond to a question or prompt, solve a math or science equation, share what’s still confusing them, or any other quick assessment strategy. After class, the teacher reviews the answers to see if everyone has mastered the task or they need a little more guidance.

Try it: 26 Exit Ticket Examples and Ideas

What are your favorite instructional scaffolding examples? Come exchange ideas in the We Are Teachers Helpline group on Facebook.

Plus, check out these Creative Ways To Check for Understanding.